The Constitution For The United States

Its Sources and Its Application

by Thomas James Norton

(Retrieved from archive.org)

The research, work, and dedication

Of

Barefoot Bob Hardison

August 8th, 1933 - January 31st, 2009

![]()

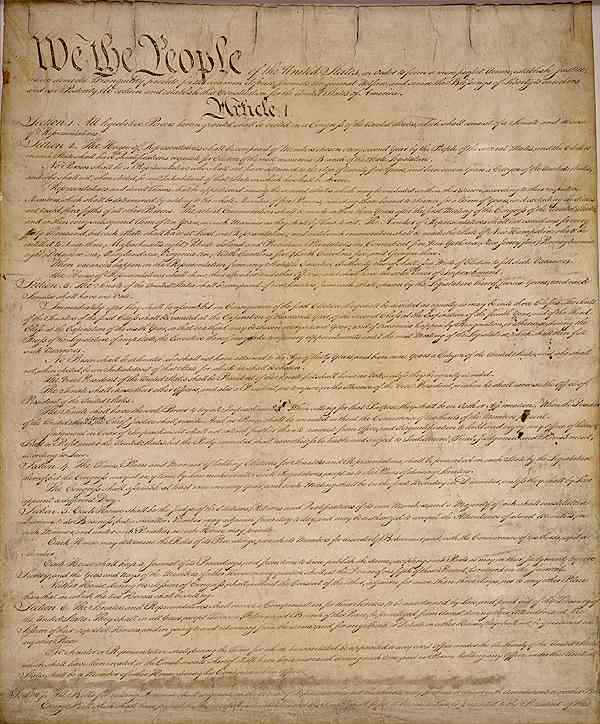

The Constitution For The United States

Its Sources and Its Application

Contents

Preamble

Article 1

Article 2

Article 3

Article 4

Article 5

Article 6

Article 7

Ratification

1st 12 Amendment Proposals

"Bill of Rights" Amend. I - X

Amend. XI -XXVII

Missing Original 13th Amendment

Letter of Transmittal

Landmark Court - Case Index

Constitution History

A Quiz for Loyal Americans

Index

Article VII

Section 1. The Ratification of the Conventions of nine States shall be sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution between the States so ratifying the Same. 137

137 As the Articles of Confederation (Art. XIII) provided that no alteration should ever be made in them unless "agreed to in a Congress of the United States and be afterwards confirmed by the legislature of every State ," this complete superseding of the Articles by the action, not of "a congress," but of a Constitutional Convention, and the ratifying of that action by nine States instead of every one of the thirteen, has been described as revolutionary. However, the people ratified the Constitution as prepared, and it was within their power to make any change that seemed desirable. It has been seen129 that the provision requiring unanimity of State action was in practice destructive of government. It was the belief in the Constitutional Convention that the new instrument could not at first secure the approval of every State. That was correct. The Constitution went into operation with George Washington as President and a Congress of two Houses sitting before North Carolina and Rhode Island ratified it. "To have required the unanimous ratification of the thirteen States," wrote Madison in "The Federalist," . . . "would have marked a want of foresight in the Convention which our own experience would have rendered inexcusable." There was much debate over a proposal that the Constitution be submitted for ratification to the legislatures of the States instead of to "conventions," but the proposal was rejected. Some feared that the legislatures might not ratify. It has been seen, however 129, that amendments to the Constitution may be ratified in either way.

On September 20, 1787, three days after the Constitutional Convention had finished at Philadelphia the drafting of a Constitution, a copy of the new instrument was laid before the Congress, sitting in New York, accompanied by a letter from George Washington, who had presided over the Convention. "And thus the Constitution," he wrote, referring to the many conflicting opinions and interests which had been adjusted, "which we now present is the result of a spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensable." Congress at once sent a copy of the Constitution, with a copy of Washington's letter, to the legislature of each State and urged the calling of ratifying conventions. Then began the great battle in each of the thirteen States over ratification. The little State of Delaware, the only fear of which had been removed by the grant of a vote in the Senate equal to that of the largest State 18, 131, was the first to ratify, on December 16, less than three months after the Constitutional Convention adjourned. But in Pennsylvania, New York, Massachusetts, Virginia, and Maryland the opposition was strong and it had able leadership -- although most of the objections raised look unimportant now when viewed in the light of experience. It was objected that the vote in each House of Congress was to be by individuals instead of by States; that Congress was to have an unlimited power of taxation; that too much power was given to the National judiciary; that paying the salaries of senators and representatives out of the National treasury would make them independent of their own States; that an oath of allegiance to the National Government was to be required; that laws impairing the obligation of contracts were to be prohibited: that the document was the production of "visionary young men," like Hamilton and Madison; that the election of members of the House of Representatives for so long a term as two years would be dangerous; that the new Congress might make itself a perpetual oligarchy and tax the people at will; that a National capital in so vast an area as ten miles square (the District of Columbia), independent of the State, would foster tyranny; that the power to maintain an army would bring oppression; that Congress would use the power granted with respect to elections to destroy freedom of the ballot; that assent, should not be given to the continuance of the slave trade until 1808; that the Constitution contained no bill of rights, and that it gave no recognition to the existence of God.

Ratification was vigorously opposed by such men as Patrick Henry, Benjamin Harrison, John Tyler, and Richard Henry Lee of Virginia. Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, Luther Martin and Samuel Chase of Maryland, Thomas Sumter of South Carolina, and George Clinton and Melanchton Smith of New York.

While much pamphleteering and debating was done in Pennsylvania and elsewhere, the great battle was waged in New York. Not only was that State necessary to the Union because it lay between northern and southern States which had already ratified and which could not, be close commercially or politically if divided by a foreign State, but more than two thirds of the members of the convention called in New York to ratify or reject were opposed to the Constitution. Alexander Hamilton conceived the idea of explaining each part of the Constitution in a series of short articles which appeared in different publications. James Madison and John Jay aided in the work. Of the eighty-five letters published and signed Publius, five were written by Jay, twenty-nine by Madison, and fifty-one by Hamilton. They helped to carry the day, and New York entered the Union on July 26, 1788, of which it became the Empire State. In book form those letters are known as the "Federalist," the most brilliant work on our Constitution. During the French Revolution, which followed ours, the "Federalist" was translated into French. Later it appeared in German during dreams of a republic. It appeared in Spanish and Portuguese in South America, for fifteen republics south of us framed constitutions after ours. While the correspondence of the time throws much light upon the workings of the Constitutional Convention, the sessions of which were secret, like those of the British Parliament, the main source of information is the Madison Papers or the Madison Journal, made up from the shorthand notes of the great delegate from Virginia. Congress caused the publication of the notes in 1843.

"No man could say whether argument or interest had won the fight for the Constitution," says Woodrow Wilson ("A History of the American People" Vol. 3, p. 98), referring to the "Federalist" and the other discussions of the time, "but it was at least certain that nothing had been done hastily or in a corner to change the forms of Union. These close encounters of debate had at least made the country fully conscious of what it did. The new Constitution had been cordially put through its public ordeal. All knew what it was and for what purpose it was to be set up. Opinion had made it, not force or intrigue; and it was to be tried as a thing the whole country had shown itself willing to see put to the test."

DONE in Convention by the Unanimous Consent of the States present. 138

138 Rhode Island was not present. While there was "unanimous consent of the States present," some delegates of States refused to sign. For New York the only signature was that of Alexander Hamilton.

Only fifty-five of the sixty-five delegates chosen by the States sat in the Constitutional Convention. Of those, forty-two were present at the signing. Three of those present (Randolph and Mason of Virginia and Gerry of Massachusetts) refused to sign because they believed that too much power was taken away from the States.

the Seventeenth Day of September in the Year of our Lord, one thousand seven hundred and Eighty seven and of the Independence of the United States of America the Twelfth. IN WITNESS whereof We have hereunto subscribed our Names, 139

G°. Washington

Presidt and deputy from Virginia

Attest: William Jackson, Secretary.

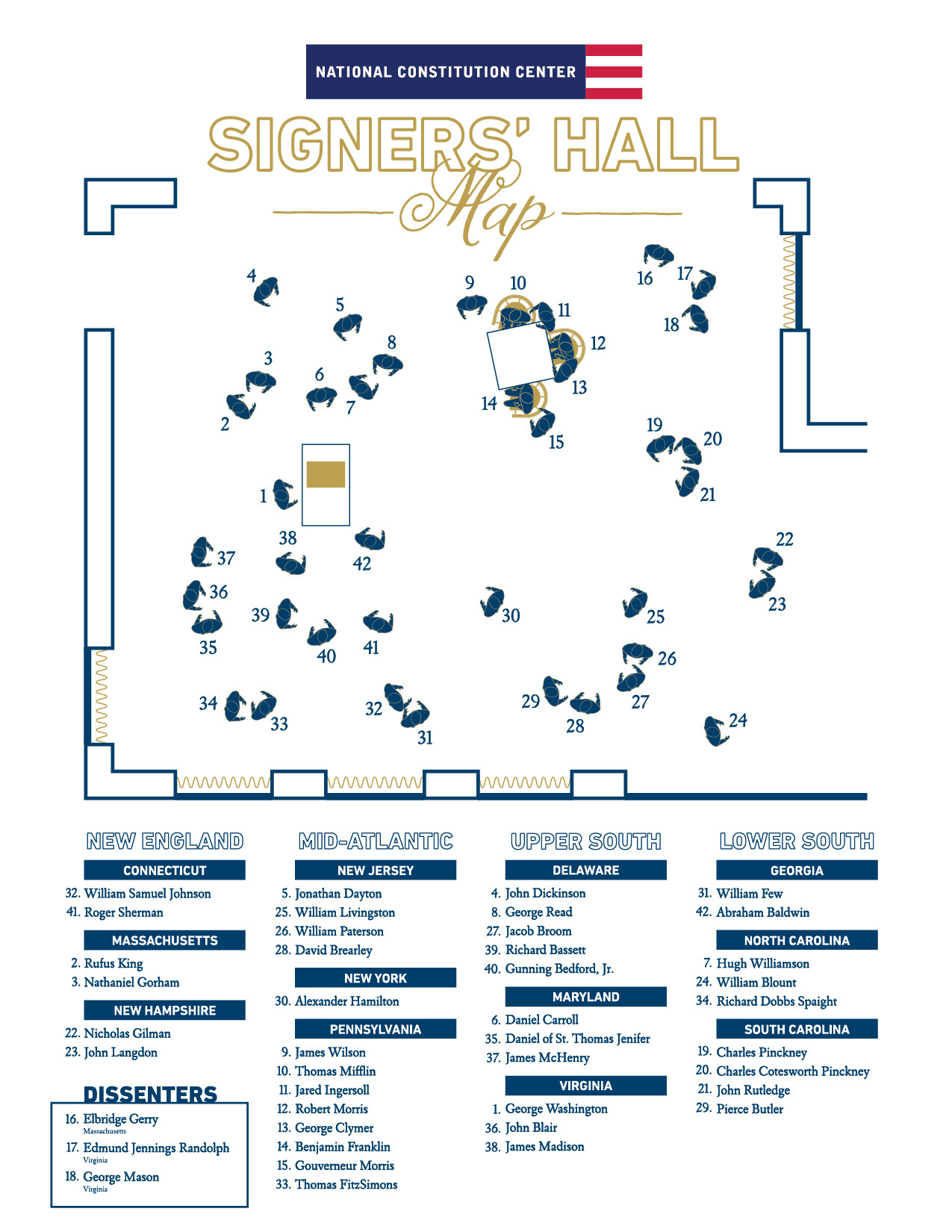

Click the under-dashed links below for biography and pictures. Click the picture for a bigger view and if there's a big X on the bottom right click that for the biggest view.

Use the Signers' Hall Map to locate the position of each signer's statue at the National Constitution Center.

Delaware

Maryland

Virginia

North Carolina

South Carolina

Georgia

New Hampshire

Massachusetts

Connecticut

New York

139 "Thus after four months of anxious toil," says Fiske ("Critical Period of American History" p. 304), "through the whole of a scorching Philadelphia summer, after earnest but sometimes bitter discussion, in which more than once the meeting had seemed on the point of breaking up, a colossal work had at last been accomplished, the results of which were most powerfully to affect the whole future career of the human race so long as it shall dwell upon the earth." The calculation has been made that the Constitutional Convention spent upon its task eighty-six working days.

"The establishment of our institutions," wrote President Monroe, "forms the most important epoch that history hath recorded. They extend unexampled felicity to the whole body of our fellow-citizens, and are the admiration of other nations."

"To preserve and hand them down in their utmost purity to the remotest ages will require the existence and practice of virtues and talents equal to those which were displayed in acquiring them. It is ardently hoped and confidently believed that these will not be wanting."

![]()

![]()

![]()

Disclaimer:

Some material presented will contain links, quotes, ideologies, etc., the contents of which should be understood to first, in their whole, reflect the views or opinions of their editors, and second, are used in my personal research as "fair use" sources only, and not espousement one way or the other. Researching for 'truth' leads one all over the place...a piece here, a piece there. As a researcher, I hunt, gather and disassemble resources, trying to put all the pieces into a coherent and logical whole. I encourage you to do the same. And please remember, these pages are only my effort to collect all the pieces I can find and see if they properly fit into the 'reality aggregate'.

Personal Position:

I've come to realize that 'truth' boils down to what we 'believe' the facts we've gathered point to. We only 'know' what we've 'experienced' firsthand. Everything else - what we read, what we watch, what we hear - is what someone else's gathered facts point to and 'they' 'believe' is 'truth', so that 'truth' seems to change in direct proportion to newly gathered facts divided by applied plausibility. Though I believe there is 'truth', until someone representing the celestial realm visibly appears and presents the heavenly records of Facts And Lies In The Order They Happened, I can't know for sure exactly what "the whole truth' on any given subject is, and what applies to me applies to everyone. Until then I'll continue to ask, "what does The Urantia Book say on the subject?"

~Gail Bird Allen

![]()

![]()

-

Urantia Book, 44:0.11 - The Celestial Artisans

Never in your long ascendancy will you lose the power to recognize your associates of former existences. Always, as you ascend inward in the scale of life, will you retain the ability to recognize and fraternize with the fellow beings of your previous and lower levels of experience. Each new translation or resurrection will add one more group of spirit beings to your vision range without in the least depriving you of the ability to recognize your friends and fellows of former estates.

-

Princess Bride 1987 Wallace Shawn (Vizzini) and Mandy Patinkin (Inigo Montoya)

Vizzini: HE DIDN'T FALL? INCONCEIVABLE.

Inigo Montoya: You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means. -

Urantia Book, 117:4.14 - The Finite God

And here is mystery: The more closely man approaches God through love, the greater the reality -- actuality -- of that man. The more man withdraws from God, the more nearly he approaches nonreality -- cessation of existence. When man consecrates his will to the doing of the Father's will, when man gives God all that he has, then does God make that man more than he is.

-

Urantia Book, 167:7.4 - The Talk About Angels

"And do you not remember that I said to you once before that, if you had your spiritual eyes anointed, you would then see the heavens opened and behold the angels of God ascending and descending? It is by the ministry of the angels that one world may be kept in touch with other worlds, for have I not repeatedly told you that I have other sheep not of this fold?"

-

Urantia Book, Foreword - 0:12.12 - The Trinities

But we know that there dwells within the human mind a fragment of God, and that there sojourns with the human soul the Spirit of Truth; and we further know that these spirit forces conspire to enable material man to grasp the reality of spiritual values and to comprehend the philosophy of universe meanings. But even more certainly we know that these spirits of the Divine Presence are able to assist man in the spiritual appropriation of all truth contributory to the enhancement of the ever-progressing reality of personal religious experience—God-consciousness.

-

Urantia Book, 1:4.3 - The Mystery Of God

When you are through down here, when your course has been run in temporary form on earth, when your trial trip in the flesh is finished, when the dust that composes the mortal tabernacle "returns to the earth whence it came"; then, it is revealed, the indwelling "Spirit shall return to God who gave it." There sojourns within each moral being of this planet a fragment of God, a part and parcel of divinity. It is not yet yours by right of possession, but it is designedly intended to be one with you if you survive the mortal existence.

-

Urantia Book, 1:4.1 - The Mystery Of God

And the greatest of all the unfathomable mysteries of God is the phenomenon of the divine indwelling of mortal minds. The manner in which the Universal Father sojourns with the creatures of time is the most profound of all universe mysteries; the divine presence in the mind of man is the mystery of mysteries.

-

Urantia Book, 1:4.6 - The Mystery Of God

To every spirit being and to every mortal creature in every sphere and on every world of the universe of universes, the Universal Father reveals all of his gracious and divine self that can be discerned or comprehended by such spirit beings and by such mortal creatures. God is no respecter of persons, either spiritual or material. The divine presence which any child of the universe enjoys at any given moment is limited only by the capacity of such a creature to receive and to discern the spirit actualities of the supermaterial world.

-

Urantia Book, 11:0.1 - The Eternal Isle Of Paradise

Paradise is the eternal center of the universe of universes and the abiding place of the Universal Father, the Eternal Son, the Infinite Spirit, and their divine co-ordinates and associates. This central Isle is the most gigantic organized body of cosmic reality in all the master universe. Paradise is a material sphere as well as a spiritual abode. All of the intelligent creation of the Universal Father is domiciled on material abodes; hence must the absolute controlling center also be material, literal. And again it should be reiterated that spirit things and spiritual beings are real.

-

Urantia Book, 50:6.4 - Planetary Culture

Culture presupposes quality of mind; culture cannot be enhanced unless mind is elevated. Superior intellect will seek a noble culture and find some way to attain such a goal. Inferior minds will spurn the highest culture even when presented to them ready-made.

-

Urantia Book, 54:1.6 - True And False Liberty

True liberty is the associate of genuine self-respect; false liberty is the consort of self-admiration. True liberty is the fruit of self-control; false liberty, the assumption of self-assertion. Self-control leads to altruistic service; self-admiration tends towards the exploitation of others for the selfish aggrandizement of such a mistaken individual as is willing to sacrifice righteous attainment for the sake of possessing unjust power over his fellow beings.

-

Urantia Book, 54:1.9 - True And False Liberty

How dare the self-willed creature encroach upon the rights of his fellows in the name of personal liberty when the Supreme Rulers of the universe stand back in merciful respect for these prerogatives of will and potentials of personality! No being, in the exercise of his supposed personal liberty, has a right to deprive any other being of those privileges of existence conferred by the Creators and duly respected by all their loyal associates, subordinates, and subjects.

-

Urantia Book, 54:1.8 - True And False Liberty

There is no error greater than that species of self-deception which leads intelligent beings to crave the exercise of power over other beings for the purpose of depriving these persons of their natural liberties. The golden rule of human fairness cries out against all such fraud, unfairness, selfishness, and unrighteousness.