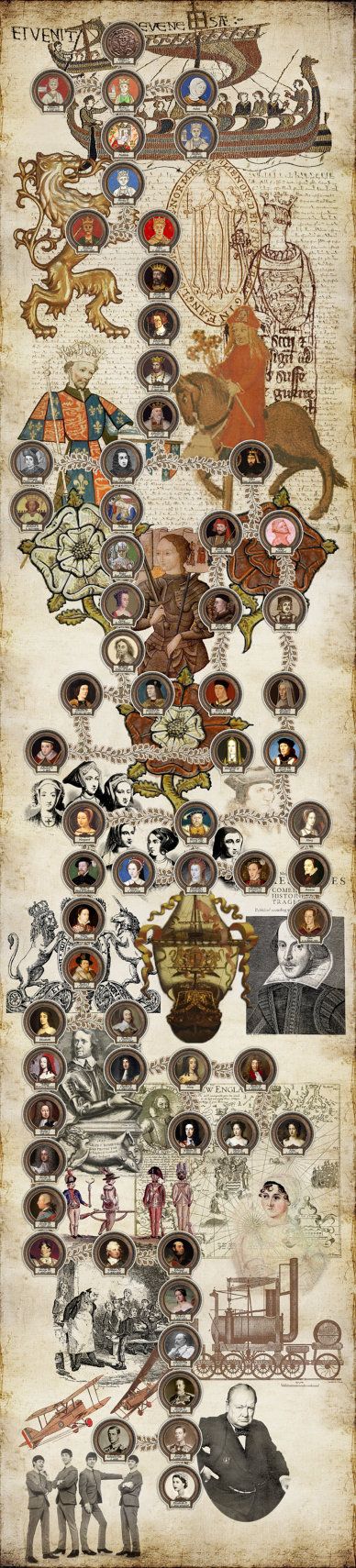

THE CONQUEROR & HIS SUCCESSORS

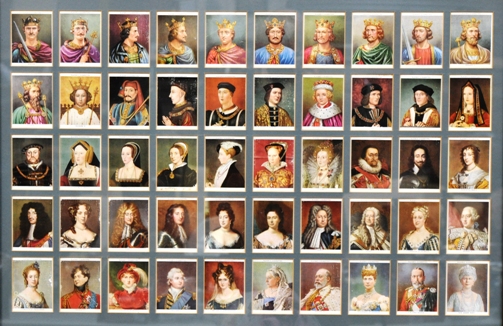

from William to Elizabeth III

WILLIAM of Normandy, called "THE CONQUEROR" and "THE GREAT" and "ANOTHER CAESAR", one of the great men of history, obtained to the English Throne in 1066 following the death of Edward "The Confessor" after defeating and slaying King Harold II in the Battle of Hasting, and deposing the boy-king Edgar II "Aetheling," the last Old English king, which began the Late Middle Ages in England. William was the first English monarch of the House of Normandy. He was the greatest general of his time, and never lost a battle.

The House of Normandy was founded about 150 years earlier by William's ancestor, the viking-leader Rollo or Hrolf "The Walker" [Hrolf "Ganger," or Gongu-Hrolf], who was so large that no horse could carry him, who, and his gang of viking-pirates, called "North-Men" or "Normans," operating out of their pirate fort at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, made raids in Britain, Ireland, and France. The Vikings were permitted by the King of France to settle in the French province of Neustrie [which then became Normandy], which was given to Rollo [Hrolf "Ganger"] as a fief of the French Crown, who, thereupon, became the first Duke of Normandy (911). Normandy from its beginnings was a vigorous military state, and Rollo and his descendants made it into the most formidable state in Europe. The Viking colony of Normans in France were the most aggressive and expansionist race in Europe at that time. The Normans, however, eventually adopted the French culture and language and thus over the course of time were absorbed by the native French population. The ancestors of Rollo were Viking sea-kings descended from the famous viking-leader Ogier "The Dane" [Holger "Danske"], who was a scion of the Scyldings of Denmark. Ogier "The Dane" was onetime briefly recognized as "King of England" (796), thus, the accession of William represented the restoration of the Viking Dynasty which had earlier conquered England and had established itself on the British Throne, succeeding the Anglo-Saxon Bretwaldas but had since been dispossessed by the restoration of the heirs of the old Anglo-Saxon bretwaldas as the Kings of England or the Old English Royal House, which dynasty William overthrew. The struggle between the Vikings and the Anglo-Saxons was fought over 300 years before finally coming to an end with the victory of William "The Great" at the battle of Hastings.

Sometimes called "The Bastard," William was the illegitimate son of Duke Robert "Diablo" or "The Devil," of Normandy, of his mistress Herleve [daughter of Fulbert of Falaise], the wife of Herluin of Conteville, by whom she was the mother of two other sons, Eudes (Odo) and Robert, and of a daughter, Muriel. In those days bastards were still eligible for the succession in the absence of a legitimate heir, for the Church had not yet stepped in to disqualify illegitimate off-spring. There is a story that Duke Robert fell in love with Herleve, a young girl, whom he one day saw washing clothes in a stream as he looked out from his castle. He wooed her, and she became his mistress and in due course William was born. Alice was probably Robert's daughter also by Herleve. William was reared by his step-mother Margaret [formerly Estrid], the half-sister of King Canute "The Great" of England, who, by Robert, was the mother of a daughter, Felica, William's half-sister. Margaret already had three sons begotten of her late husband Ulph, a Swedish prince, who were: Sve[g]n [the future King Sven II of Denmark], Osborn [the Seneschal of Normandy], and Bjorn. Margaret died shortly after her divorce from Duke Robert following seven years of marriage, and Robert died himself soon afterwards leaving William an orphan at age seven or eight. On the death of Duke Robert "Diablo" of Normandy, his comrades Alan of Bretagne, Gilbert of Brionne, and Osborn, the Seneschal of Normandy, took custody of the little eight year-old boy-duke William from the protection of the King of France at the French court at Paris. They became the guardians of the boy-duke, William, but all three were murdered and a twelve-year period of anarchy followed during which William found himself in a chaotic situation. The boy-duke changed hands several times to protect him from would-be assassins, and in a turn of events came into the care of the English prince Edward ["The Confessor"], who was himself an exile in Normandy at that time. Edward, whose mother was William's great-aunt, secretly fostered William during his exile in Normandy, and took William to England with him upon returning home from exile at the invitation of the new English king, his half-brother, King Hardeknut. It was William's second visit; for his first visit to England had been about ten years earlier as a young child with his father Duke Robert and his step-mother Margaret (Estrid) to see the boy's step-uncle, King Canute "The Great," who liked the boy and William became King Canute's favorite, and was once overheard to have said that "one day the boy would have it all"; a remark that proved to be prophetic. Edward succeeded his half-brother Hardeknut as King of England the same year that William came of age, 1042, and in the absence of his own issue King Edward adopted his foster-son the teenage William as his heir; and later in 1057 compelled the English nobles to swear an oath to support him. That year, 1042, William returned from England to Normandy with English soldiers to claim his inheritance, and after five years of fighting William finally overcame the rebel Norman nobles and took possession of Normandy in 1047 as its duke, William II.

Though the English nobles had years earlier sworn an oath to Duke William of Normandy acknowledging him as the heir of King Edward "The Confessor," however, upon King Edward's death in 1066 the English nobles ignored their oaths and elevated Earl Harold of Wessex to the English throne as King Harold II even though he was not in the line of succession. Duke William contested the election of King Harold by the English nobles and sent a letter to Pope Alexander II in Rome asking for his judgment concerning the matter; and the pope sent William a letter authorizing him to establish his claim, and also sent along a banner under which to fight for his rights, which William understood to have been a promise from God of victory.

Duke William, with the pope's blessing, gathered an army from every quarter of France and collected an armada of ships and set sail across the English Channel with his own ship in the lead under the banner of Christ [given to him by the pope] waving at the masthead [and later carried into battle by the army] and landed unopposed in England in early autumn. Three weeks later the English Army arrived and William "The Norman" engaged and defeated the English Army and slew the English King Harold II in the Battle of Hastings. William, after resting his army for five days at Hastings, set out for London. His progress was slow and cautious, and a bout of dysentery that ran through the army held up the march for a month. Meantime, the "witanagemot" meeting in London elevated the "rightful heir," Prince Edgar "Aetheling" to the throne as King Edgar II of England. After a short siege, London surrendered to William, who deposed the boy-king Edgar II, who was obliged to abdicate in William's favor; and Duke William took possession of the English kingdom. The Norman Conquest is commemorated on the 240-foot-long "Bayeux Tapestry" embroidered by William's queen Matilda and her ladies-in-waiting. It tells the life-story of William in pictures and highlights his victory at Hastings. [note: the "Bayeux Tapestry" is technically an embroidery not a tapestry since all tapestries are woven.]

On Christmas Day [25 December] Year 1066 William "The Conqueror" [age 39] was crowned King of England in Westminster Abbey in London in a ceremony officiated by [E]Aldred, the Arch-Bishop of York, since Stigand, the Arch-Bishop of Canterbury, refused to take part. The coronation placed William in the succession of the old English kings, but it was followed by measures which showed that England was a conquered country. William desired to reign not as a conqueror but as the "rightful" king, however, the rebellion of the English under the heirs of the old royal house transformed William from a king into a conqueror. Nationwide rebellion forced William to hold by the sword what he had won by the sword. It wholly changed his position from his "adoptive right" to the "right of conquest." It took several years and a campaign of terror to subdue the whole country. England was harried by William with such deliberate savagery that it took over a century for the country to recover economically from the Norman Conquest. The Normans during that period had to live like an army of occupation and built motte-and-bailey forts all over the country; and among them William built the Tower of London as his residence on the site of an old Roman fort originally built by Julius Caesar, "Caesar's Citadel"; and, built Windsor Castle in the English countryside outside London. Throughout his reign, William was putting down sporadic outbursts of rebellion by the English people.

Nearly all the English nobles were compelled to surrender their rank and estates to the Normans, for since William claimed to have been the rightful king from the time of the death of King Edward "The Confessor" all those nobles who had supported King Harold [whom he regarded as an usurper] were considered traitors and consequently their estates were confiscated and given by William to his "companions," all of whom were foreigners; and French-speaking Normans replaced the English-speaking Anglo-Saxon aristocracy in England. These were the ancestors of the great families of Medieval England, who became the dukes, marquises, and earls of England's great estates. William also replaced English bishops with foreign ones, among whom Stigand, the Arch-Bishop of Canterbury, was replaced with the Italian bishop Lanfranc of Pavia, formerly the Abbot of St. Stephen's at Caen in Normandy.

The English state was re-organized by William in his policy of "Normanization," the likes of which had not been seen in Britain since the Roman Conquest. William abolished the four great Anglo-Saxon earldoms, that is, Wessex in Southern England, and East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria in Northern England, which left the shire, or county, as the largest unit of local government which all now became fiefs of the crown, and their rulers, the local lords, [now] called "barons" [= dukes, marquises, and earls], became the vassals of the king. All the king's vassals and their knights were summoned by King William to meet with him on Salisbury Plain around Stonehenge where in a midnight ceremony they all with torch fires burning solemnly swore an oath of fealty to William [and his heirs] as their liege lord to whom they bound themselves [and their descendants] by a contract. It was called the "Salisbury Oath."

A "great council" was summoned to meet by King William as a forum to settle the affairs of the country which was called the "King's Court" ["curia regis"], out of which was to evolve parliament as well as the great departments of government which gradually moved out of the "King's Court" to become institutions of state themselves which left the royal household to cater for the domestic needs of the royal family.

Feudalism, the economic system of land tenure then prevalent on the European continent, was introduced by William and it replaced the original tribal structure of English society. The concept of "territorial sovereignty"[in contrast to "tribal sovereignty"] was here introduced and the king now became the supreme landowner "par excellence." The king owned the whole country, but leased out its lands to his vassals or tenants-in-chief, who in turn sub-let their lands to their knights. Thus, each land-holder owed service, feudal dues, and personal allegiance to his over-lord, and, so on, to the king. As the author of "1066 and All That" aptly put it "everybody had to belong to somebody else and everybody else to the king." The feudal system in its ideal represented an organic hierarchy in which its members varied a balanced obligation with the king who stood at the top of the feudal-pyramid over the nobles who provided the knights for the king's service who were all supported by the labor of the "serfs" [the common people]. The Normans enslaved the Saxons in "serfdom" for several hundred years.

A massive audit of the country's wealth was conducted by William to be used for purposes of taxation in the "Great Survey" which was recorded in the "Domesday ["Doom's-Day] Book," so called for the survey seemed like "Judgment Day" to the subjugated native Saxon population. The like had not been seen before in Britain since the Roman Era, and was unequalled in its comprehensiveness and detail until the nineteenth century.

After conquering England, William invaded Wales (1067) and conquered the eastern half of the country and established the Welsh March (1068), which was a chain of shires [earldoms] along the English-Welsh border. They were: Chester, Shrewsbury, and Hereford. He appointed Hugh "The Wolf" of Avranches, as the Marquis of Chester; Roger Montgomery as the Marquis of Shrewsbury; and William FitzOsbern as the Marquis of Hereford (1067). Hugh "The Wolf" from Chester Castle pressed into Northern Wales. The commander of his forces, Robert of Rhuddland, established himself in Rhuddlan Castle from where he led attacks against Gwynedd. Roger Montgomery established himself in the frontier castle of Montgomery, whence he conducted attacks on the Welsh midlands and conquered Powys. And, William FitzOsbern, from Hereford Castle, crossed into Southern Wales and conquered Gwent and built Chepstow Castle. [The conquest of Wales in 1284 made the Welsh March irrelevant, but it was not abolished until 1536.] Later, William overran the western half of Wales (1071), traversed the country, and received the submission of the regional Welsh kings and took the title "Lord of Wales." William also invaded Scotland (1072) and defeated the Scots and received the submission of the Scottish nobility as well as the Scottish king and took the title "Lord of Scotland."

The Normans were masters of Britain after subjugating the English, Welsh, and Scots. Their influence extended far beyond their Norman homeland in Northern France to not only Britain but to just about all parts of Europe. The Normans under William's second-cousin, Robert "Guiscard," completed the expulsion of the Byzantines from Western Europe (1059), warred with the Holy Roman Empire, took Rome, expelled the Emperor Henry IV and also Pope Clement III and pillaged and looted the city for three days (1084) before the Normans withdrew to their camp in Southern Italy, which became the Norman dukedom of Apulia, from where they attacked Greece, the Near East, and Africa. The principality of Antioch, in Syria, was founded by the Normans. The Normans during William's reign engaged in trade with their colonies in the Mediterranean, those in the North and Baltic Seas, as well as with those in the North Atlantic, that is, Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland (Canada).

In his capacity as Duke William II of Normandy, King WILLIAM I of England was a vassal of the King of France, and, thus, the Kings of England as simultaneously Dukes of Normandy were Peers of France. The successors of the House of Normandy on the English throne, the houses of Blois and Anjou, were also vassals of the French kings, and the English kings of those dynasties in their capacity as French vassals usually evaded the difficulty created by the demands of the French kings for homage for their French fiefs by investing their sons with those possessions and sending them to France to do homage to the King of France, and the problem was eventually resolved upon the inheritance of the French Crown by the English Royal House, after which the Kings of England were simultaneously the Kings of France [or claimed to be] from King Edward IIII to King George III [who dropped the title when France became a republic].

Tall, thick-set, and "strong as an ox," William was shrewd, ruthless, and stern beyond measure. He was not a man to be trifled with, so that no one dared do anything contrary to his will for fear of him. He inspired loyalty among his followers and fear among his enemies.

The wife and queen of King William "The First," "The Conqueror," was Matilda of Flanders, the daughter of a Flemish count. It was Matilda's second marriage. Her first husband had been a Flemish commoner named Gherbod by whom she was the mother of two children, a boy, Gherbod, to whom William gave an English earldom, and a girl Gundred, who was given in marriage to one of William's old cronies William de Warenne. There was some legal difficulty that delayed the marriage of William and Matilda for a number of years after it was first proposed which may have been that Matilda's first husband was still alive or possibly that she at the time was betrothed to Brihtric Meaw, an Anglo-Saxon noble; nevertheless, whatever the problem was it appears that it was not resolved before their marriage for when their marriage finally did take place it was held to have been irregular by church authorities. They had a pre-marital illegitimate daughter, Sylvia. Their marriage produced five sons and six daughters, of whom only three sons and four daughters survived their parents. Matilda was totally devoted to William, despite his three indiscretions that produced two illegitimate sons and one illegitimate daughter. His eldest son, Robert "Curthose," rebelled against him and fought a series of battles against King William in a civil war between father and son.

The last years of King William's life, he was engaged in civil war with his eldest son, Robert "Curthose." Prince Robert, supported by the King of France and the French garrison at Mantes, where Robert "Curthose" had established his headquarters, made a raid into Normandy, to which King William retaliated by attacking the city. And, during the sack of the city his horse stumbled on a hot cinder and flung him. He sustained grave internal injuries from being thrown from his horse, and, after suffering several days, died at the Priory of St. Gervais, near Rouen, Normandy, in 1087 [age 60] in the twenty-first year of his reign. He was buried in Normandy at Caen in the Abbey of St. Stephen, which he had earlier built. His tomb was despoiled during the French Revolution, 1790s, and his bones were scattered and lost, except his thigh bone which was reburied in 1987 under a new tombstone in front of the altar in the Abbaye aux Hommes. A slab marks the site of his original tomb in St. Stephen‘s Abbey. Since his eldest son Robert was in rebellion against him, and his second-son Richard had been killed in a hunting accident six years earlier, William, before his death, gave his third son, William "Rufus," a letter addressed to the Norman barons designating Rufus as his heir over Robert. The death of William "The Conqueror" left a disputed succession, not only among his sons; but the English longed for the restoration of the ex-king, Edgar II "Aetheling". This gave rise to a national trauma of identity, in a country whose population was made-up of three different races, that is, the Norman-French (Vikings), the Anglo-Saxons, and the Celto-Roman Britons (Welsh). The situation was not helped by the general unpopularity of the Norman dynasty in England, whose only supporters were their Norman-French barons. The legacy of William "The Conqueror" was immense. He founded a new dynasty, a new English state, introduced a new economic system, reformed the English Church, and introduced a new culture.

WILLIAM II, called "RUFUS" or "THE RED" for his flaming red hair and ruddy complexion, was accepted as king by the Norman barons of England over his elder brother Robert, and succeeded his father on the English Throne in 1087 (age 30) over the objections of his half-uncle, Eudes (Odo), Earl of Kent, who organized a rebellion to place Robert on the throne, but which was brutally crushed by Rufus thus securing him in the kingdom (1088). Rufus is one of the villainous kings of English History. He was stormy, violent, cruel, savagely harsh, vicious, untrustworthy, deceitful, treacherous, obnoxious, crude, rude, and uncivilized in his behavior. His more endearing characteristics (so to speak) were his cynicism, wittiness, and sarcasm. His rule was despotic and oppressive which of course made him unpopular with the English people. Unlike his father who was always above reproach in his dealings, Rufus exploited his position for his own benefit. The people suffered in poverty and were taxed to the point of starvation while Rufus and his court enjoyed a lavish life-style reveling in all sorts of vice. The extravagance of his court was in marked contrast to the austere conditions of his late father's court. And, the debaucheries of his court shocked the nation. King Rufus was rebuked by Arch-Bishop Anselm of Canterbury for immorality and for the debauchery of his court; and Rufus threw the Primate out of England into exile. It was written in the "Anglo-Saxon Chronicle" that "everything that was hateful to God and to righteous man was the daily practice in this land during his reign." Rufus was irreverent and blasphemous and was particularly fond of anti-religious jokes. He had a foul mouth, and blasphemed with almost every sentence. His hostility to Christianity was clear by his persecution of the Church and its clergy in England during his reign. His prime minister, Ranulf Flambard, carried-out all of Rufus' policies. Rufus reviled and treated the clergy with such contempt that the nation's priests fled the country; thereupon, Rufus helped himself to church revenues. Rufus laughed with scorn at his excommunication by the pope. There were grumblings of dissension throughout the country, and repeated efforts to overthrow Rufus were thwarted by his secret agents. One such rebellion was led by Robert Mowbray, Earl of Northumberland, who attempted to oust Rufus and place Stephen of Albemarle, a relative of the royal house, on the throne, however, as all the other attempts it too was ruthlessly swashed by Rufus.

Meantime, most of Wales was grabbed up by Norman barons who conquered native Welsh regional-kingdoms and in their place founded Norman earldoms. Hugh "The Wolf," Earl of Chester, used Cheshire as a base to attack the Welsh. Roger de Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury, penetrated deep into Wales and conquered Merioneth which he renamed after himself. William Fitz Osbern, Earl of Hereford, established outposts at Monmouth and Chepstow and annexed Gwent. The Earl of Clare, a Norman noble, landed at Milford Haven and pushed back the Welsh and founded a Norman colony in Pembrokeshire. Robert, the Castellan of Rhuddlan, conquered Conwy-Denbighshire (Clwyd). Bernard of Neufmarche conquered Brecon [Brycheiniog] and carved-out a state for himself in the central part of Wales. Philip de Braose seized Radnor (1090), and moved on into Buellt and established himself there. Roger de Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury, overran Ceredigion and conquered Dyfed [Deheubarth]. He established the lordship of Pembroke, which he handed over to his brother, Arnulf de Montgomery. William Fitz Baldwin conquered Carmarthen. Robert Fitz Hamo[n], Earl of Gloucester, landed in Morgannwg (Glamorgan), overran the Welsh state 1090-1091, deposed its last king, Iestyn II, and divided up the country among his knights. The lordship of Monmouth was given to "Fitz Baderon"; the lordship of Ewyas to Hugh de Lacy; and, the lordship of Abergavenny to "de Ballon." Resistance against the Normans was led by the ex-king Iestyn II of Glamorgan [Morgannwg], who, following a period of guerrilla-warfare, was defeated in battle by the Normans under Robert Fitz Hamo[n] at Mynedd Bychan, near Cardiff, and sought refuge in a priory at Llangenydd in Gower, where he died from his wounds (1093). The Norman barons displaced the native Welsh rulers, and collected the taxes which hitherto had been rendered to them. Old Welsh royals held out in scattered pockets throughout Wales. The lordship of Avon was granted to Caratoc, the son of the late king Iestyn II, the last King of Morgannwg [Glamorgan], and his descendants adopted the family name of "Avene." The senior-line of the descendants of King Iestyn II of Morgannwg took the surname "Lougher" around 1500, and the family still flourishes today!

During his reign, King Rufus suppressed a rebellion in Normandy (1090), twice invaded Scotland to quell uprisings (1091 & 1093), and suppressed a rebellion of the Welsh (1098). He led an army to Cumbria, defeated Dumnail (Domhnuil), its last native king, and annexed Cumbria to England in 1092.

In 1092, in Ireland, during a rebellion of the Irish chieftains, who had been at enmity with one another over the Irish succession since the time of Brian "Boru," when the high-kingship had passed from the O'Neills to the O'Briens and the O'Conors. The tribal chiefs and clan captains of Ireland gathered in an assembly and drew up a document of grievances and sent it to the Pope along with items of the royal Irish regalia, including the ancient crown of the Irish high-kings itself [which was made of gold and embedded with emeralds] authorizing him to appoint a successor. This was to have far-reaching results in the later reign of King Henry II, unforeseen at that time.

In 1093 a serious illness frightened Rufus into repentance, however, as his health improved he became his same old self again. Rufus was accidentally killed or perhaps murdered while out hunting in the New Forest by an arrow shot by one of his companions, Walter Tyrell [husband of Alice de Clare], who fled to the continent and was never heard of again. The probability of murder is great. It was very likely plotted by the family of De Clare in the interests of the king's younger brother, Prince Henry, who was in the same hunting party. Prince Henry left King Rufus's body where it fell and hurried back to court and seized the royal treasury and usurped the throne during the absence of his elder brother, Robert "Curthose"; while King Rufus's body was transported by some peasants on a farm cart to Winchester Cathedral arriving the next morning with blood dripping from it the whole way. Rufus was buried in the cathedral directly below the main tower with little ceremony, the clergy denying him religious rites. William II "Rufus" died in 1100 (age 43) unwed and without legitimate issue in the thirteenth year of his reign. His death was a relief to the English people who had suffered so miserably during his reign.

HENRY I, called "BEAUCLERC", meaning "fine scholar," because he was well-educated and bookish beyond the norm of his time. He could read and write in three languages: French, English, and Latin. He was the only one of The Conqueror's sons to be born in England. This, and the fact that he spoke English gave him an advantage over other contenders in public opinion. Henry seized the throne (age 32) upon the death of his brother William II "Rufus" in 1100 during the absence of his elder brother Robert "Curthose," who had joined Godfred of Bouillon in the First Crusade (1096-1099). Godfred of Bouillon conquered Palestine with troops from all over Europe and founded the medieval crusader-kingdom of Jerusalem. Henry "Beauclerc" was crowned "King of England" three days after his brother's death in London at Westminster Abbey, by Maurice, the Bishop of London. Robert "Curthose" returned the next year a hero from the Holy War and challenged the succession of his younger brother Henry during his absence, and civil war broke out between the two brothers (1101-1106). Prince Robert was defeated by King Henry in battle at Tinchebrai, captured, and imprisoned in Cardiff Castle for life. He spent 30 years in prison, and died, probably starved, and was survived by a son, William "Clito," who was considered by the Normans as the rightful heir.

It was Henry's first act as king to issue a charter promising good government, which was very much welcomed after his late brother's oppressive reign, and it gained Henry the favor of the English people. He imprisoned Ranulf Flambard, his late brother's prime minister; and recalled Anselm from exile to re-take his office as Arch-Bishop of Canterbury and English Primate. Henry appointed gifted and able men to office; such as Roger Salisbury, whom he appointed chancellor, which was what the "prime minister" was called in those days. He organized a department at court for the collection of royal revenue, and founded the court of the "Exchequer" to administer finances. The exchequer sat at a table with counters and a checkered table-cloth was used to facilitate counting, carefully checking with the sheriffs the taxes, rents, fines, and debts due to the crown. Every penny had to be accounted for. The office of "exchequer" was deputized by King Henry to oversee the sheriffs [royal agents] of the country's shires. King Henry began the practice of keeping the records of the accounts of the sheriffs and other royal officials in each shire rolled up in metal pipes, hence, they were called "Pipe Rolls." The "Pipe Rolls" are the longest series of English public records dating from 1100 to 1834.

King Henry institutes administrative reforms in government for which he was called the "Lion of Justice." He greatly extended the scope of the "King's Court" ["Curia Regis"] which paved the way for its evolution into parliament. He reformed the judiciary, overhauled the tax-collection system, and established a civil bureaucracy. The administration of the country was centralized in the royal court, which also doubled as a supreme court overseen by a "Justiciar" [which office King Henry created], who was made the chief-judge over all of the country's law-courts. Henry, of course, as king, was the supreme-judge, to whom any of his subjects customary may appeal their case. King Henry also established the system of itinerant judges dispatched from the royal court to the country's localities.

The country's churches were allowed to re-open by King Henry who restored all the bishops, priests, and vicars to their offices; and King Henry patched up things with the pope apologizing for the abuses of his late brother. Henry tried to establish good relations with the pope, but came into conflict with the pope over the question of the investiture of the clergy in their offices. For the pope had granted his father, William The Conqueror, the right to invest his own bishops; but had no wish to extend the concession to his sons, which gave rise to the "investiture controversy."

It appears that Henry was a likable king. He was said to have been of average height, fair-looking, with a well-built physique. His coolness, presence of mind, and calm composure contrasted sharply with the high charged emotional temperament of either his late brother or his late father, although like them Henry was capable of great cruelty and could be very ruthless. He was a firm, exacting king; and, a strict enforcer of the law. Too, he was a shrewd politician as portrayed in his marriage to the Saxo-Scot co-heiress Edith of Athole [who changed her name to the Norman-sounding "Matilda"], the daughter of King Malcolm III of Scotland and St. Margaret, the sister and heiress of the ex-king EDGAR II "AETHELING," the last of the old line of English kings. The marriage, of course, was politically motivated for it robbed the claims of the Scottish line to the English throne of much of its force, for the children of St. Margaret, the English heiress, were regarded by the English people as representing the older royal race and thus were rival claimants of the Norman kings to the English throne. The marriage won King Henry immense popularity among the English people and helped to remove any doubts about the legitimacy of the Norman succession. Henry kept on good terms with his wife throughout their eighteen-year marriage despite the fact that he had numerous mistresses and numerous illegitimate children. Their first-born, a son, died premature at birth (1101); another son, William "Aetheling," was born the next year (1102); and lastly a daughter, Matilda, was born the following year (1103).

A revolt of the Norman barons in Wales broke out in 1108, and the forces of King Henry I reduced the palatine earldom of Shrewsbury, which was then converted into the shire of Shropshire. On his march to Pembroke Henry I took Carmarthen where he built a castle, which became the chief royal centre in South Wales. The Bishop of Salisbury, King Henry's "justiciar," was given the lordship of Kidwelly; and, to the Earl of Warwick was granted the lordship of Gower. The Lord of Clifford, advancing from Brecon, established himself in Landovery where he built his castle. The lordship of Cemaes, with its castle at Nevern, and later at Newport, was given to Fitz Martin of Tours. Ceredigion was granted to Gilbert FItzRichard de Clare of Clare Manor in Suffolk, who built his castle at Cardigan. Only Cantref Mawr in South Wales remained to the native Welsh ruler, Gruffydd, King of Deheubarth. Thus the greater part of Deheubarth was lost to the Welsh; but after the death of King Henry I in 1135 the Welsh seized the opportunity by the outbreak of civil war in England between Queen Matilda [King Henry I's daughter] and her cousin King Stephen [King Henry I's nephew] to rise up against the Normans. And, the Welsh drove the Normans out of their estates. In South Wales, the Welsh successfully drove out most of the Normans and re-established the Kingdom of Deheubarth. In North Wales the Welsh of Gwynedd drove the Normans almost to the borders of Chester.

The English succession was thrown into confusion by the early death of Prince William at age eighteen or nineteen, who tragically drowned with his entourage in the wreck of the White Ship in the English Channel off Barfleur while on his way back to England from Normandy, which duchy his father had bestowed on him (1120). He had gone to France to be formally invested as Duke of Normandy by King Louis VI of France, and on his return to England he and his entourage had barely set sail when the ship, steered by drunken helmsmen, struck a rock and wrecked. It was a terrible blow not only to King Henry but to the whole English nation. After the death of Prince William [called "Aetheling" as the heir of the old English kings] the other Prince William [called "Clito" as the heir of the Norman dukes], the son of King Henry's elder brother Robert "Curthose," was generally considered to be the heir to the throne. The ex-king Edgar II "Aetheling" was still alive, and, there was still support for him in England for his restoration. He was invited back to England by King Henry who gave him an estate in England for his residence. For the ex-king by then had become a childless elderly gentleman who never had married due to his life-long military-career as a "free-lancer." William "Clito," a hot-blooded, ambitious young man, raised a rebellion and was killed while attempting to overthrow his uncle, King Henry, and take the throne by force. Henry, three years after the death of his queen, Matilda (Edith) of Scotland (1118), married secondly (1121) Adeliza of Louvain in the hope of begetting another male heir, but their marriage did not produce any children. Henry had nine illegitimate sons and sixteen illegitimate daughters, but bastards were by this time disqualified from the succession or any inheritance from their parents. Henry, accepting the fact that he was unlikely to produce another male heir, declared his daughter MATILDA as his heiress, and bribed the barons with lavish gifts from the royal treasury to support her (1126). She had just returned to England from abroad following the death of her husband, the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V, the last of his line (1125). They had a daughter, Christina, but no sons. Matilda was still within her child-bearing years and since she had been declared heiress it was important for her to remarry and hopefully beget a male heir. She was betrothed to the ex-king EDGAR II in 1126, but he died just before their marriage. King Henry had the remains of the late ex-king Edgar II laid to rest with his ancestors in Winchester Cathedral [formerly called the "New Minister"], which was a great gesture to the English Nation on his part. The death the ex-king Edgar II, in 1126, nullified his betrothal to marry King Henry's daughter, Matilda; and in stead she married (1127) as her second husband Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, thus, reinforcing the continental drift of the monarchy, and by him was the mother of three sons, the eldest of whom was the future King Henry II.

Still distraught over the death of his only male heir, King Henry became a somber and sad figure in his remaining years. It is said that after the wreck of the White Ship he never smiled again. Henry I died in 1135 (age 67) in the thirty-fifth year of his reign. He was buried in Reading Abbey, Berkshire. His tomb was destroyed during the republican era, 1650s. The "ASC" says that Henry "was a good man, held in great awe." Henry I ought to have been succeeded by his daughter Matilda but the feeling was so strong at the time among the Norman barons against the rule of a woman that despite the pledge of the barons to support her succession the barons instead raised her cousin Stephen to the throne.

STEPHEN (age 39) usurped the throne on the death of his uncle King Henry I [his mother's brother] in 1135 in prejudice of his cousin MATILDA, King Henry I's daughter, the legal heir, who was out of the country at the time, and was upheld by the Norman barons who reneged on their oaths to Matilda and officially elected her cousin Stephen king. Stephen was the son of Etienne-Henri, the Count of Blois, and Adela, the only one of The Conqueror's daughters to have children. Adela's husband died while their children were still young, and Stephen as a boy was brought up by his mother, the head-strong daughter of William "The Conqueror," in the English Court of his uncle [her brother] King Henry I; and Stephen became his uncle's favorite. Stephen was made Count of Mortain in the English Peerage by King Henry I, his uncle. Stephen was the only English monarch of the House of Blois.

The House of Blois was a French noble house of Norse ancestry which [according to one theory] descended from the Viking Sea-King Sholto (750), whose ancestry is a mystery to this author, who some genealogists say was the ancestor of three great descent-lines, which were: (1) the French House of Blois [its 2nd dynasty]; (2) the Scottish clan of Douglas; and (3) the Irish MacDougils. The son of Sholto, namely, William, accompanied Charlemagne on his Italian campaign (774). Another genealogy makes the ancestor of the House of Blois to have been the Viking-Leader Gerlon, the leader of a war-band of Vikings, descended from Ogier "The Dane," who was appointed governor of Blois by the King of France (920), who founded Blois' 3rd dynasty. These two origin-stories doubtless represent two separate foundings of the County of Blois by two separate dynasties, Dynasties Two and Three. There is another origin-story of the County of Blois that makes the ancestor of its first dynasty to be Ivomadus, a Gallo-Roman general in the service of the British Emperor Constantine II [III-RE] who occupied Blois in AD 410. The provincial-governor Aguyvus "Le Blois" is reckoned to have been one of his descendants. The names of three generations of the first dynasty of the Counts of Blois are known to be (a) Hugues, Count of Blois (d534); (b) Melaudon of Blois (d560), and (c) Beleis (Abelechin) "Le Voir" (d593). Their genealogy as far as this author knows has never been researched or reconstructed from medieval records. The genealogies of the second and third dynasties of Blois are also unsure in their early stages, and puts in question which descent-line is the true male-line of the house.

His queen, Matilda of Boulogne, bore Stephen three sons and two daughters. His second-son Eustace became his heir on the death of his first-born son Baldwin at age nine; and his third-son William became his heir on the death of Prince Eustace at age twenty-two. Stephen also had illegitimate issue, as was expected of kings in those days. Stephen has been described as a "good-natured, warm-hearted, open-handed, and a chivalrous gentleman," however, he was a weak ruler, politically inept, and lacked many of the qualities necessary for kingship. The nobles recognized these weaknesses in King Stephen and exploited them to their own advantage. King Stephen was quite unable to control the feuding Norman barons, and the country collapsed into disorder. There was a rebellion of the Norman barons in 1136, the year following King Stephen's usurpation. As late as 1137 there was an English plot which was foiled to drive the Normans out of England and hand over the English crown to either of several claimants of the Old English Royal House, namely: (a) Malcolm "MacHeth," Earl of Ross [son of Ethelred, Abbot of Dunkeld, who had been debarred from the succession]; or (b) Harold, the eldest son of the late King Edgar of Scotland and his wife Ealdgyth, daughter of Maldred, Lord of Carlyle & Allerdale; or (c) King David "The Saint" of Scotland, whose mother had been "Saint" Margaret, the English heiress, sister of the ex-king Edgar II "Aetheling." Most of the reign of King Stephen, described as "nineteen long winters," was occupied in a civil war to keep the throne against his cousin Matilda, the lawful queen, while England fell into anarchy and into the prey of the Norman barons who robbed villages, looted abbeys, and terrorized its people into paying exorbitant taxes.

from History of England

by St. Albans Monks

MATILDA, called "THE EMPRESS", as the widow of the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V, and, called "LADY" [of England] as the daughter and heiress of her late father, the Norman King Henry I of England, was regarded as the rightful successor to the throne by the majority of the English people. She contested the usurpation or election of her cousin Stephen in 1135, but it was not until 1139 that she was able to come to England to claim her inheritance. She gathered forces on the European continent and came asserting her claim to the English Throne. The allegiance of the barons split on her arrival in the country, and civil war broke out. Matilda after a hard fought campaign at length overcame Stephen at the Battle of Lincoln and entered London in triumph to the cheers of its citizens. King Stephen was deposed by a council held at Winchester [7 Apr. 1141] and imprisoned in Bristol Castle; and Matilda, England's Empress, was proclaimed "Lady of England" (age 38). In those days a king was usually styled "lord" or in the case of a queen "lady" before his or her coronation, though fully sovereign. Queen/Empress Matilda reigned only seven months [Apr.-Nov.]. The country took an immediate dislike to her. There was something about her that brought out the worst in people. Her rule was harsh and the heavy taxes she levied made her very unpopular. She alienated most of her supporters, and enthusiasm for her cause quickly faded away. She was arrogant and tactless; and was so proud, haughty, and superior-acting that soon everyone came to be disgusted with her. And, before her coronation, the citizens of London rose up in rebellion against Queen/Empress Matilda and drove her out of the city and sent deputies to offer the throne back to the ex-king Stephen. A period of anarchy followed and civil war again broke out between Empress Matilda and King Stephen. The civil war was finally brought to an end through the efforts of the Church by a compromise in which King Stephen was allowed to keep the throne for life but lost the succession for his son Prince William in favor of Empress Matilda's son Count Henry. The ex-queen Empress Matilda left England in 1147/48 and returned to the continent and lived abroad as the reigning duchess of Normandy. She was England's last Norman monarch. The ex-queen Empress Matilda died some years later (1167) (age 64) and was buried first in the convent of Bonnes Nouvelles, and later transferred to the Abbey of Bec. Her remains were later removed to Rouen Cathedral, where a brass plate marks her grave.

STEPHEN [of Blois] reigned a second time upon his restoration in 1141 following the expulsion of Empress Matilda and his release from prison. He was unable to gain control of affairs, and the country slide back into anarchy. King Stephen, a sad figure, died in great agony from acute appendicitis in 1154 (age 59) in the nineteenth year of his reign and was buried in Faversham Abbey, Kent; and, in accordance to a legally binding pact was succeeded by Empress Matilda's son Duke Henry who became King Henry II.

HENRY II, called "CURTMANTLE" for a short cloak he wore [that set a new style in men‘s clothes], also called "FITZ-EMPRESS" after his mother, was the son of Matilda, Lady [Queen] of England, and the French Count of Anjou, Touraine, and Maine. Henry II "Curtmantle" succeeded to the throne in 1154 (age 21) on the death of King Stephen [his mother's cousin] as per according to a pact, or "testament," made by his mother, Empress Matilda, with King Stephen. Henry II was the first English monarch of the House of Anjou, the Angevins, which was also called "Plantagenet" [= "planta genista," meaning "sprig of broom," which was a bright yellow blossom], a nickname for a helmet decoration worn by King Henry II's father, Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, instead of a feathered plume which was usually worn on helmets. King Henry II has been described as a stout, red-headed, athletic man with a cracked voice.

The House of Anjou was a French noble house of royal Gallic ancestry. Geoffrey of Anjou, the dashing prince-consort of England's queen Matilda, descended in the male-line from Geoffrey "Ferole" of Chateau-Landon, Count of Gatinais, ancestor of the third Angevin dynasty, who descended from Warin, the twin brother of Mille [the ancestor of the Capetians of France], the sons of Robert, Duke of Hesbaye, the grandson of [another] Warin, Count of Paris, the brother of St. Leger, Bishop of Autun, and, Didion, Bishop of Poitiers, another brother, the three sons of Bodilon [and wife, Sigrade, his niece], who descended from Torquatus [Torquate], the first Count of Anjou (513), the founder of the first Angevin dynasty, one of the original "Twelve Peers of France," the grandson of Syagrius, the last Roman Governor of Gaul, who descended from old pre-Roman Gallic kings, e.g., Ambiorix "The Heroic Gaul" (58-53BC), Akichorix, King of Gaul (300-250BC), Ambigatus, "the Celtic Charlemagne" (500BC), who were themselves descended from the old Iron Age Celtic emperors, e.g., Albiorix "Galates," the son of the Greek hero HERCULES and Galatea Keltine, Queen of Gaul (1200BC), only child and daughter of Narbos Celtae (1250BC), the last male-line descentdant on the Old Celtic Royal House founded by Samothes (2050BC). Thus, the Angevins ["Plantagenets"] of England and the Capetians of France were collateral-lines of an ancient dynasty of pre-Roman Gallic kings who were the cousins of the ancient Macedonian-Greek kings, as well as the Thessalian kings, the co-kings of Sparta, and also of other Classical Greek dynasties. The Angevins ["Plantagenets"], appear later divided into two major branches, namely, the houses of Lancaster and York, which fought the "War of The Roses." The 1st Angevin dynasty was restored to its ancient estate after an interim as the 3rd Angevin Dynasty succeeding the 2nd Angevin Dynasty, which the Plantagenets also represented through intermarriage. The 2nd Angevin dynasty was founded by Tertulle [Tertullus] of Rennes, who possibly may be identified with [or have been the son of] Tortulfe "The Woodsman" of Nid-de-Merie, called "a soldier of fortune," and, his wife, Melusine, called "the Devil's Daughter" in local lore because she was non-European by race and non-Christian in religion and was rumored to have practiced witchcraft and the "black arts," hence, the tradition arose that the Plantagenets were "Satan's Spawns." It was said of the Plantagenets that "from the Devil they came and to the Devil they will return." Tertulle of Rennes is however usually regarded as the son of Hugh, Count of Bourges, Auxerre, and Nevers, which would make him a scion of the House of Alsace and the Ethiconides. Tertulle founded the 2nd Angevin dynasty following the Viking Wars that swept away the 1st Angevin dynasty. The descendants of Tertelle, the 2nd Angevin dynasty, ended with an heiress, Ermengarde, Countess of Anjou, who married Geoffrey "Ferole," Count of Gatinais (above), descended from the 1st Angevin dynasty who became the ancestor of the 3rd Angevin dynasty.

Before he became King of England Henry "Plantagenet" was already ruler of half of France. He had become Duke of Normandy which was resigned to him by his mother (1150), and had become Count of Anjou, Touraine, and Maine, on the death of his father (1151), and had come into possession of several other French provinces by marriage (1152) to the heiress of those estates, Eleanor of Aquitaine, which included Aquitaine (Guyenne), Poitou, Gascogne, Auvergne, Perigord, Limousin, and La Marche, over which Henry exercised overlordship. Bretagne (Brittany) came under Henry's domination with the later marriage of its heiress to one of his sons. These territories formed the Angevin Empire. It left the domain of the King of France to only the Il-de-France and its surrounding counties as an isle in a sea of the Angevins' possessions. Eleanor's family also had claims to the fiefs of the Count of Toulouse which Count Henry prepared to enforce by force of arms, but King Louis VII of France threw himself into Toulouse and Henry shrank back from fighting his suzerain as a vassal of the French Crown, and withdrew from Toulouse (1159). England was but a part of the far wider Angevin Empire, and not necessarily the most important part, for the early Angevin kings were very much attached to their French dominions and roots. Each dominion had its own government and each was ruled according to the customs of that domain, and the king's court ["curia regis"] provided the administrative unity for all of the dominions. Henry II was very energetic and traveled ceaselessly about his extensive domains. It helped that Henry II spoke several languages such that he was able to communicate with all of his feudal lords in their own native languages. Henry II thus was more of an European ruler than an English king. The fact that English kings held lands in France dominated English foreign policy for hundreds of years; and, in consequence, it postponed any attempt to fashion a united kingdom of the British Isles.

Ireland, Wales, and Scotland were subdued by King Henry II during his reign, and he held sway over the whole of the British Isles. Not since Canute "The Great" had any English king exercised overlordship over the whole British Isles. King Henry II inherited claims to the overlordships of Wales and Scotland, however, he was content during his early reign to secure stable relations with the native rulers of those countries. His intervention in Ireland in 1171 was even designed to contain the Anglo-Norman adventurers already there in the interests of the Irish native rulers. Henry had considered an Irish venture of conquest in 1155 after the pope issued the papal bull "Laudabiliter" (1154), which gave Ireland to England, but delayed the venture for an opportune time. The authorization by which The Holy See had given Ireland to King Henry II of England in 1154 was based on a document drawn up by an assembly of Irish chieftains in 1092 which had entrusted the Irish crown to The Holy See; hence, from 1092 to 1154 Ireland was technically a fief of The Holy See. The Pope in 1154 even sent King Henry II the royal Irish regalia, which had been entrusted to The Holy See since 1092, to recognize him as "King of Ireland" and successor of Irish Kings. The opportunity came when the Irish provincial king Dermot IV of Leinster, who had been driven from his kingdom by a civil war, came to Angers Castle, Anjou, France [the dynasty's seat], and appealed to King Henry II of England for help. Henry sent a company of soldiers to Ireland in 1169 to restore Dermot in Leinster, which gave the Anglo-Normans a foothold in Ireland. The Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169 was not an English invasion, for the English were still not assimilated by the predominantly French-speaking Norman-Angevin Empire, and conflicts were still erupting between Norman overlords and their English vassals. In 1170 Richard de Clare "Strong-Bow," Earl of Pembroke, came in force with a great army of mercenaries, or Norman adventurers. They were joined by forces under Maurice Fitz-Gerald, Robert Fitz-Stephen, Maurice Prendergast, Hervey de Montmarish, Raymond Fitz-William "Le Gros," Miles de Cogan, William Fitz-Adelm, Philip de Braose, John de Courcy, Robert de Bermingham, William de Barri, and others, who landed with Norman, Welsh, and Flemish forces. More troops were sent to Ireland in the following months. A force under Richard de Clare, Earl of Pembroke, defeated and slew Ostell, the 37th and last Viking-King of Dublin, ending the Danish kingdom of Dublin in 1170 and establishing the English lordship [earldom] of Dublin with de Clare as the first Lord of Dublin. Meantime, in Ulster, Conchobar II, the 55th King of Ailech; Murchad ua Cerbaill, the 83rd King of Airgialla; and Magnus, the 90th King of Ulaid, were all defeated in battle in 1170 fighting English troops. The marriage of Richard de Clare to Aeoifa, the daughter of Dermot IV, the 78th King of Leinster, left de Clare as King of Leinster in right of his wife upon King Dermot's death in 1171. Meantime, Dermot's son, Domnall [V] "Caemanach," the last native King of Leinster, set himself up as king in opposition to Richard de Clare, and opposed him until his death (1175). Richard de Clare hastily returned to England to appease the jealousy of King Henry and gave Dublin to the English Crown, and did homage for Leinster as an English lordship, giving up the title "king" in exchange for the title "earl" in recognition of King Henry's overlordship as one of his vassals. He accompanied King Henry II who proceeded to Ireland in 1171 in the "great Anglo-Norman invasion," with 400 ships carrying 5000 soldiers, to assume control over the Irish campaigns of his Anglo-Norman adventurers. Henry II invaded Ireland with an Anglo-Norman Army and spent six months campaigning in Ireland and thus laid the foundations of what became English rule. He defeated the Irish in a series of battles, and the whole country surrendered to King Henry in a mass submission. Mael Sechlainn II, last King of the Deisi, was among the Irish "provincial-kings" who fell in battle. The Irish High-King, that is, Ruaidri II [Rory O'Connor], the King of Ireland, after his defeat in the Battle of Dublin against the Anglo-Normans, went about collecting troops from all parts of Ireland to resist the invaders, and to make a stand for the independence of the nation. This show of resistance did not last long, for Ruaidri II, exhausted, came to realize that he could not sustain the war any longer, and when he heard that the Irish "provincial kings" had deserted him and had put themselves under the protection of the King of England he sent messengers to the English king to make peace and acknowledged his overlordship, and surrendered along with all of the Irish provincial kings and regional chiefs, among whom were: Domnall IX "Breagach," the 67th and last King of Meath; Cathal VI "Crobderg," the 70th and last King of Connaught; Domnall II "Mor," the 66th and last King of Munster and the 1st Earl of Munster; Domnall [V] "Caemanach," the 80th and last King of Leinster; and, Prince O'Neill, Aedh "an Macaemh Toinleasc," the royal Irish heir. He established himself as King of Ulster in 1176 but was killed the next year in 1177 fighting an English force under John de Courcy. The last king of Ulster's 2nd Dynasty was Ruaidri [Rory Mac Donslevy], the 99th King of Ulaid [IIB], who was succeeded by the son of the late Prince O'Neill who styled himself Aedh X "Meth," who consolidated the O'Neills in Ulster as Ulster's 3rd Dynasty (1201).

King Henry held court at Dublin, where he received the submission of the Irish "provincial kings" who all made a pact with the English king and pledged to be his vassals. The Irish provincial kingdoms all became English lordships in 1172 and the heirs of their old royal houses dropped their title "king" to become earls in the English Peerage. Ruaidri II, the last native "King of Ireland," did not immediately loose his throne. Ruaidri II concluded a treaty with Henry II whereby he and all future Kings of Ireland would hold the Irish kingdom as a fief "in capite," as vassals of the English crown. Thus, Ruaidri II became vassal-king of Ireland with Henry II of England as overlord, and had to pay tribute annually. And, in a "parliament" or assembly of the Irish chieftains at Lismore it was solemnly determined that the kings of England would, in all future time, be lords [overlords] of Ireland, whereupon King Henry II of England took the title "Lord of Ireland," and English kings were styled "Lords" of Ireland from 1172 to 1541 when Henry VIII changed the style to "King."

The feudal system of government was introduced in Ireland by Henry II modeled on England's administrative system. King Henry partitioned Ireland among his barons. Gilbert de Angulo was given Meath. The province of Connaught was given to William FitzAdelm. Dublin was given to Hugh de Lacy. Waterford was given to Robert de la Poer, who divided it up among Humphrey de Bohun, Robert FitzBernard, and Hugh de Gundeville. Limerick was placed under the lordship of Herbert FitzHerbert, who resigned and conferred the lordship to Philip de Briouze. Robert FitzStephen and Maurice FitzGerald were made the city's co-adjudicators. Robert FitzWilliam was given command of the English troops in Ireland, usually stationed at Dublin. Ulster was given to John de Courcy. These Norman barons over the years forged marriage alliances with native Irish rulers, and were culturally "gaelicized" over the course of time. The "gaelicized" Norman barons of Ireland came to be increasingly independent of the mother-country, and centuries later rose up in rebellion against the English crown.

King Henry wintered in Ireland. He held a synod of all of Ireland's bishops at Cashel early in 1172 to reform the country's religion from its native brand of Celtic Christianity to Roman Catholicism, which was attended by a papal legate, Vivianus, dispatched by the pope, who made known to the Irish clergy the papal bull, called the "Laudabiliter" [so-called from the first word of its Latin text], granting Ireland to King Henry II and his successors, and, who introduced to Ireland the payment of "Peter's Pence" annually to Rome. It was forgotten that the church in Ireland at this time had been in conflict with Rome for many centuries. Later, in 1186, the pope sent to King Henry II the royal Irish crown to confirm him in the Fiefdom of Ireland. It was the same crown that had been given to an earlier pope by the deposed and exiled Irish king, Donchad O'Brien, and his enormous entourage, in 1064. The crown had been entrusted to the Roman Catholic Church for the pope to bestow it upon whomever he may choose. That year, 1186, Henry II thought to bestow the kingship of Ireland on his son, John; for he had already crowned his eldest son, Henry, as "King of England" in 1170, demonstrating that England and Ireland were regarded by King Henry only as provinces of the Angevin Empire, centered in Anjou (cap.: Angers), in France.

By spring, urgent affairs called King Henry II to England though he had not planned to depart Ireland until summer. However, before his departure, King Henry II appointed Hugh de Lacy as the first of a series of English governors of Ireland who were to rule the country in the name of the Kings of England for the next 750 years (1172-1921).The Governor of Ireland sat at Dublin, which surrounding counties was called "the English Pale." His authority was rarely recognized outside The Pale, and the native Irish chiefs, now earls in the English Peerage, continued to govern their ancient estates. Ruaidri II, King of Ireland, tried to strengthen his bond with the Norman conquerors by marrying his daughter, Aoeifa, to Ireland's first "English" governor, Hugh de Lacy; and, declared Aoeifa to be his "banchomarbae" ["female-heiress"]. Hugh de Lacy quelled an Irish uprising in 1175 that led to the "Treaty of Windsor" (1175), the terms of which obliged the last native Irish High-King Ruaidri II to designate Henry II of England as his "tanist" [heir]. Ruaidri II traveled to London and signed the Treaty of Windsor in 1175 acknowledging English overlordship, and gave homage to King Henry II as his suzerain. The Irish subjects of King Ruaidri II grew tired of him in the following years, and he came to be very unpopular in his own country among his own people, and he was deposed in 1183 by his sons, who each contented for the Irish high-kingship in a civil war against their father and then among themselves. It was an ignominious end to Ireland's last native high-king. The ex-king Ruaidri devoted the last thirteen years of his life to monastic seclusion at Cong Abbey, where he died at the advanced age of 82 in 1198 un-mourned and long forgotten by his former subjects. The Irish King Ruaidri II was survived by a daughter Aoeife, whom he had designated his heiress, wife of the English Governor, Hugh de Lacy [his 2nd wife]. Through their issue a descent-line may be traced to later English kings, through the Earls of Ulster. Henry II was himself descended from Irish royalty through his grandmother Edith of Athole, whose family was a Scottish branch of the Irish Royal House [the O'Neills].

Upon returning from Ireland King Henry campaigned in Wales and obliged the Welsh kings to drop their title "king" and adopt the title "prince" in recognition of his overlordship, and Wales became an English principality in 1172. Henry also retook Cumberland, Westmoreland, and Northumberland from the King of Scotland and re-established the northern border of England along the mountain-line of the Cheviots, and campaigned in Scotland, forced the submission of its king, and Scotland became an English fief in 1174.

As one of the greatest European medieval kings, King Henry II of England was offered the imperial crown of the Holy Roman Empire as well as the crown of the Crusader-Kingdom of Jerusalem [as a relative of its royal house also] but declined to accept either invitation. [The Crusader-Kingdom of Jerusalem at the time was suffering from difficulties per the succession to its throne which led to the disintegration of the kingdom and its conquest by the Saracens, i.e., Muslims, under Saladin, which prompted another crusade to recover the kingdom in the next generation led by King Henry's son, Richard "The Lion-Heart."]

A number of important legal reforms were enacted by Henry II and among them were changes he made in the judicial system which included trial-by-jury of one's equals, which was a radical concept in those days. Henry made it possible for an increasing number of cases to be heard by his judges and greatly extended the use of juries in cases heard in his courts. He dismissed incompetent sheriffs, re-established the circuit-tours of judges dispatched from the royal court to the empire‘s domains, and involved the "royal court" in policy-making [which set a dangerous precedent that enabled the "royal court" to evolve into "parliament" in later centuries ]. Henry was a man of many accomplishments. He was a strong, able king, and a vigorous administrator of his domains. His strenuous exertion of trying to hold together his vast empire prematurely aged him.

The conflict King Henry had with the Church was the setting for the movie "Becket." Thomas Becket, formerly Henry's chancellor and close companion, now Arch-Bishop of Canterbury, disagreed with King Henry over the issue of whether church ministers who committed crimes were to be tried in church courts or in state courts and resisted King Henry's attempts to persuade him otherwise, and they quarreled over the issue which ended in Becket's murder by four of King Henry's knights who heard King Henry's exasperated utterance: "is there no one who will rid me of this rogue priest?"; and took him at his word although without his knowledge. Henry had a terrible temper, was volatile, and often hasty in his words and actions. King Henry was blamed for Becket's murder by the English populace, and, though the pope had absolved him of the murder yet under pressure of public opinion Henry submitted to a humiliating public scouring by church clerics. He did public penance by donning sackcloth and ashes, undergoing a three days' fast [which alarmed his ministers], and walking barefoot in a pilgrim's gown through the streets of Canterbury to Becket's tomb where he barred his back and all the monks of the abbey chapter lashed him seven times apiece with Henry receiving hundreds of welts and wounds. This would have killed a weaker person, but Henry was a strong man, sturdily built, and was able to walk back through the streets of Canterbury and then to mount his horse and ride off back to London.

First were his quarrels with Becket, then were his quarrels with his wife, Queen Eleanor, and, then, there followed a series of quarrels with his sons. Henry II was so overbearing that he tended to alienate those closest to him. Henry, of Eleanor, had six sons and three daughters. His second-son Henry became his heir on the death of his first-born William at age three; and his fifth son Philip died soon after birth. The marriages of his daughters set-up links with the rulers of Sicily, Castile, and Saxony. His queen, Eleanor, came to hate Henry for his open flagrant infidelities. They had a stormy marriage. The couple were quite incompatible. He would do anything to irritate her; and she did her utmost to turn her sons against their father and would delight in backing first one son and then another against him. Henry also had illegitimate issue, at least six or seven sons and one or more daughters. He took advantage of his role as guardian and protector [pending the intended marriage of his eldest son, Richard, whom he despised], to seduce his son's fiancee, Alice of France, daughter of King Louis VII of France, and kept her from marrying his son, solely to spite him. His most famous mistress was Rosamund Clifford with whom he lived openly after his estrangement from his queen. His sons, stirred up by their mother Queen Eleanor, Henry II's neglected wife, rebelled against their father. The rebellion embittered King Henry against his queen and his sons [except his youngest son, John, his favorite] and he never got over it. The rebellion was crushed by King Henry in battle at Gisors, France, upon which his sons, Prince Henry, Prince Richard, and Prince Geoffrey, fled to the protection of the royal court of the King of France at Paris [who had provided troops to the three royal brothers]; and their mother Queen Eleanor was shut-up by their father [King Henry] inside Winchester Castle where she was kept under house-arrest in comfortable confinement for the next sixteen years until King Henry's death. Nonetheless, twelve years later, in 1185, during the Christmas Holidays, King Henry gathered all of his family together at Chinon Castle, in Touraine, France, to hash out their grievances which was the setting for the movie "The Lion In Winter." It was an explosive situation. They would scheme, cajole, argue, and trick their way through both real and imagined alliances. Henry duped the others, then, he, in turn, was duped by them. The quarreling went on all during the Christmas Season, and after the holidays with nothing resolved his sons went back into exile and his queen went back into comfortable confinement at Winchester Castle. His heir, Henry, called "The Young King" because he was crowned king in his father's lifetime, died while in rebellion against his father. His only child, William, begotten of his wife Margaret of France, died in infancy. The discovery that King Henry's youngest and favorite son Prince John had conspired with his older brothers against him so shocked King Henry that he fell into a quick decline and died heartbroken several weeks later in 1189 (age 56) in the thirty-fifth year of his reign. He was buried in Fontevraud Abbey, France, on the north side of the nave.

RICHARD I, called "LION-HEART" for his courage, was still in rebellion against his father at the time of his father's death yet he had the support of the people and since he was the next heir was received by the people as their king on his father's death and succeeded to the throne in 1189 (age 32). Richard "Lion-Heart" epitomizes the "Age of Chivalry." He was a soldier-king, tall, athletic, strong, and displayed the etiquette of knightly qualities. He was brave in battle, chivalrous, and ever gallant in victory. He was everything expected of a king. He was intelligent, well-educated, cultured, polished, and refined; spoke several languages, was polite, well-mannered, and courtly; and, of course, dashing, handsome, and glamorous. Richard was a brilliant general, skilled in strategy, logistics and tactics; as well as a skillful diplomat. There was another side to Richard as a romantic who wrote poetry and played music. King Richard was enormously popular and greatly admired by his countrymen. He caught the imagination of his generation and became a national hero and the subject of numerous European romantic sagas. Richard was absent from England for most of his reign fighting in foreign wars leaving England to be governed by regents.

To the detriment of the country, King Richard became obsessed with the noble aim of retaking The Holy Land from the Saracens. The year following his succession King Richard set off on the "Third Crusade" against the Saracens [Muslims] occupying The Holy Land with a large fleet carrying thousands of soldiers and left the government of the realm in the hands of William Longchamp, the Bishop of Ely, who, after King Richard had gone, was expelled by Richard's younger brother, the so-called "evil prince," John, who took over the country as regent and filled the offices of government with his circle of friends and oppressed the people with high taxes, injustice, and bad laws. To this period belongs the adventures of Robin Hood and his outlaw-band of "merry men" of Sherwood Forest. Meantime, King Richard had some remarkable military successes against the Saracens in The Holy Land. He was ruthless and struck fear in the hearts of the Saracens. His victory over Saladin at Arsouf and his capture of Acre, Jaffa, and other towns, fueled the growth of the legend of his invincibility among the Muslims. For centuries afterwards Moslem mothers would hush their children with the words: "Malek-Ric [King Richard] will get you!" [or, "the British are coming!"]. News came to King Richard of his brother's rebellion in England while besieging Jerusalem at the climax of his career. This, and the news that King Philip of France had occupied his French fiefs, made King Richard call-off the expedition and hasten home to restore his realm. A truce was concluded with Saladin, the Saracen sultan, and by its terms Saladin was left in possession of Jerusalem but had to recognize the revived Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem [with its capital now at Acre] which Richard reconstituted under the heirs of its old royal house. Richard sent his fleet on ahead and set out for home crossing Europe by land traveling incognito. He however was recognized and captured in Austria and imprisoned for fifteen months by its duke Leopold V [whom Richard had once insulted] who was in collusion with Prince John of England and with King Philip II of France. Here belongs the episode of how the minstrel Blondel de Nesle sought out Richard by traveling throughout Austria singing a song Richard was fond of until he heard the refrain taken up by Richard from a barred window in a tower of Durnstein Castle, where Richard was being held prisoner. The attempt to rescue Richard was botched up and failed, and Richard was not released until a huge ransom of 100,000 marks was paid for him by the English people, which was an enormous sum in those days [and still is these days]. It was testimony to the love for the king by his subjects that the English people willing paid the ransom. The ransom was raised and King Richard returned home. Upon returning to England, Richard banished the rebel barons but at his mother's urging pardoned Prince John, whose reckless escapades were looked upon by Queen Eleanor with indulgence. King Richard purged the government of corrupt officials and restored good government in the country. Richard, six months later, after restoring his English kingdom, appointed Hubert Walter, Arch-Bishop of Canterbury, as regent, crossed over to France, defeated the French King Philip II in battle at Freteval, and retook his French fiefs which had been seized by the French king.

Though Richard was betrothed to the French princess Alice, sister of King Philip II of France [whom his father, King Henry II, had earlier made his mistress], he married the Spanish princess Berengaria of Navarre, the two having met as teenagers. Richard did not have any children by his queen Berengaria however he did have illegitimate issue by affairs before his marriage, that is: (a) Fulque, a son, begotten by Joan de St. Pol, onetime his mistress; (b) Philip (1184-1212), a son, begotten by an early lover; and, (c) Isabel [or Elizabeth], a daughter, whose mother is unsure. Queen Berengaria joined her husband King Richard in the Holy Land in 1191; but on Richard's departure for home across Europe overland the queen took ship and traveled by sea, and the couple did not see each other again for five years, until after the ransom was paid for and his release. She, after King Richard's death, founded the Abbey of L'Epau at Le Mans, in Bigorre, France, and retired there where she spent her remaining days.

His last years Richard spent campaigning in France attempting to bring his wayward French vassals back into line. A local uprising in Limousin, one of Richard's French domains, brought him there, and Richard was shot in the shoulder by an arrow while besieging Chalus Castle, the stronghold of the rebellious Viscount of Limoges and the barracks of his county‘s militia. He made light of the wound and continued the siege, successfully taking the castle several days later. His doctor, Marchadeus, bungled the job of removing the arrow and the wound turned gangrenous and Richard died twelve days later, nursed to the last by his mother Queen Eleanor along with his wife Queen Berengaria ever vigil by his side. He drank heavily as he lay rotting with gangrene. King Richard forgave the man who shot the arrow, Bertrand de Gurdun, but after the king's death he was flayed alive and hanged by Richard's troops. Too, his doctor, Marchadeus, paid with his own life for mishandling the case. King Richard I died in 1199 (age 42) in the tenth year of his reign and was buried in Fontevraud Abbey, on the south side of the nave [opposite his father's tomb on the north side].

JOHN, the archetype of a "wicked king," called "LACKLAND" or "LANDLESS", a nickname given to him in jest which clung to him for life, usurped the throne (age 32) on the death of his brother, King Richard, in 1199, with the support of the Norman barons in prejudice of the legal heir, his nephew, Prince Arthur, the son of his late older brother, Prince Geoffrey. England along with Normandy and Aquitaine chose to support Prince John over Prince Arthur, for Prince Arthur was a minor, age eleven, and the nobles of those lands did not like the fact that his unpopular mother, Constance, the Duchess of Brittany, would become regent during his minority; while the heartland of the Angevin Dynasty, that is, Anjou, Touraine, and Maine, chose to support Prince Arthur. King John, who was notoriously cruel, violent, and ruthless, without conscience or any moral sense murdered Prince Arthur to secure himself on the throne, and imprisoned the boy's older sister, Princess Eleanor, called "Maid of Brittany," the next in line to the throne. She was held captive in Bristol Castle for 38 years, never allowed to marry, and was probably starved to death. It outraged the French vassals of King John and they revolted against him; and gave no resistance to King Philip II of France, who, seeing his opportunity here, marched in and occupied the French homeland and territories of the Angevins in 1204 which made England from that time onwards the dynasty's new home. After which England emerged as the central kingdom, and not just an Anglo-Norman province. This caused war to breakout between England and France, and King John was soundly defeated by the French king and lost all of the dynasty's lands in France except Guyenne (1205). Later John conducted another campaign in France to recover his lost French fiefs but was again defeated by King Philip II of France (1214). John, however, had success on other fronts, and suppressed a rebellion in Wales, made an alliance with Scotland, and crushed an uprising in Ireland.

It was said that unlike his tall and handsome brothers, John was short and stocky. He was spoilt in childhood by his parents, and he grew up without morals or any sense of responsibility or duty and was totally self-indulgent. He clowned during solemn ceremonies, was tactless and insulted foreign ambassadors by laughing at their unfamiliar appearance, and never missed a chance at cheating someone.

Anxious for an heir, King John annulled his childless marriage to his wife Avisa (Hadwisa), daughter of William FitzRobert, Duke of Gloucester, and married secondly Isabelle of Angouleme, who was sometimes called "Jezebel" due to her licentious conduct, and by her begot two sons and three daughters. King John also had illegitimate issue by several mistresses, of whom his most favorite was Agatha Ferrers.