History of France

100 B.C. - 1180 A.D.

From: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Gaul

Geographic-historical scope

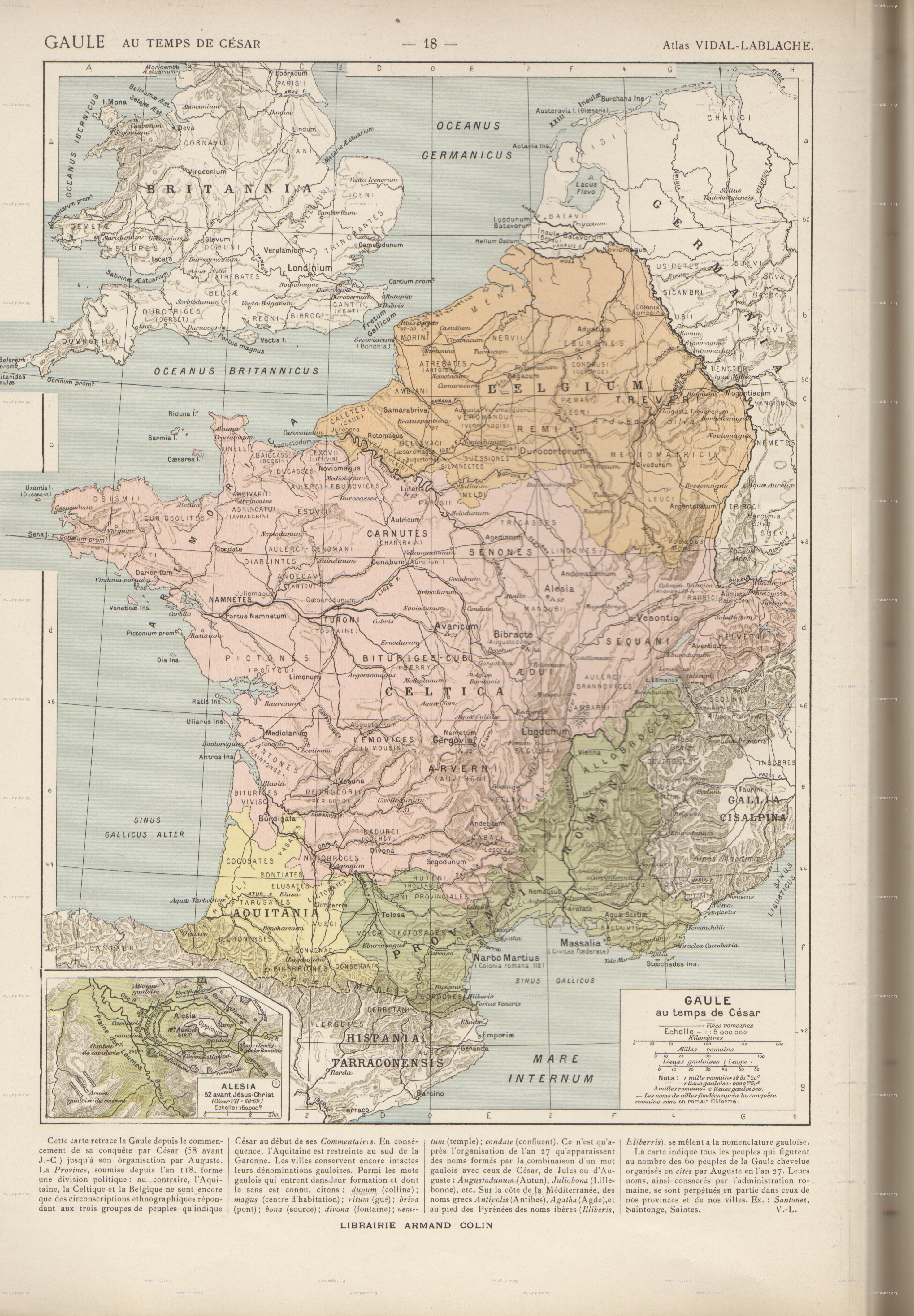

Gaul, in this context, signifies only what the Romans, from their perspective, termed Transalpine Gaul (Gallia Transalpina, or "Gaul Across the Alps"). Broadly, it comprised all lands from the Pyrenees and the Mediterranean coast of modern France to the English Channel and from the Atlantic Ocean to the Rhine River and the western Alps. The Romans knew a second Gaul, Cisalpine Gaul (Gallia Cisalpina, or "Gaul This Side of the Alps"), in northern Italy—which, however, does not belong to the history of France. Transalpine Gaul came into existence as a distinct historical entity in the middle of the 1st century BCE, through the campaigns of Julius Caesar (c. 100–44 BCE), and disappeared late in the 5th century CE. Caesar's heir, the emperor Augustus (reigned 27 BCE–14 CE), divided the country into 4 administrative provinces: Narbonensis, Lugdunensis, Aquitania (Aquitaine), and Belgica. Realizing the impossibility of large-scale expansion beyond the Rhine, rulers of the Flavian dynasty (69–96) annexed the region between the middle Rhine and upper Danube rivers, roughly the Black Forest region, to secure communications between Roman garrisons, by then permanently established on both rivers. This area was called the Agri Decumates, which may have referred to a previous settlement made up of 10 cantons. Its eastern border, conventionally referred to as the limes, assumed its final shape, as a defended palisade and ditch, under Antoninus Pius (138–161). The Agri Decumates were attached to Upper Germany (Germania Superior), 1 of 2 new frontier provinces (the other being Lower Germany [Germania Inferior]) created by the last Flavian emperor, Domitian (reigned 81–96). For greater administrative efficiency, the emperor Diocletian (reigned 284–305) subdivided all 6 Gallic provinces, forming a total of 13.

The people

Gaul was predominantly a Celtic land, but it also contained pre-Celtic Ligurians and Iberians in the south and southwest and more recent Germanic immigrants in the northeast. Neighbouring Celtic communities on the Danube and in northern Italy, however, were not included. The south, in addition, had been heavily influenced by the Greek colony of Massilia (modern Marseille, founded c. 600 BCE) and its daughter cities. In brief, the Gaul that was the foundation of medieval France was not a "natural" unit but a Roman construct, the result of a decision to defend Italy from across the Alps.

The Roman conquest

In the 2nd century BCE Rome intervened on the side of Massilia in its struggle against the tribes of the hinterland, its main aim being the protection of the route from Italy to its new possessions in Spain. The result was the formation, in 121 BCE, of "the Province" (Provincia, whence Provence), an area spanning from the Mediterranean to Lake Geneva, with its capital at Narbo (Narbonne). From 58 to 50 BCE Caesar seized the remainder of Gaul. Although motivated by personal ambition, Caesar could justify his conquest by appealing to deep-seated Roman fear of Celtic war bands and further Germanic incursions (late in the 2nd century BCE the Cimbri and Teutoni had invaded the Province and threatened Italy). Because of chronic internal rivalries, Gallic resistance was easily broken, though Vercingetorix's Great Rebellion of 52 BCE had notable successes before it expired in the cruel siege of Alesia (Alise-Sainte-Reine).

Gaul under the high empire (c. 50 BCE–c. 250 CE)

The first centuries of Roman rule were remarkable for the speedy assimilation of Gaul into the Greco-Roman world. This was a consequence of both the light hand of the Roman imperial administration and the highly receptive nature of Gallic-Celtic society. Celtic culture had originated on the upper Danube about 1200 BCE. Its expansion westward and southward, through diffusion and migration, was stimulated by a shift from bronze- to ironworking. Archaeologically, the type of developing Celtic Iron Age culture conventionally classified as Hallstatt appeared in Gaul from about 700 BCE; in its La Tène form it made itself felt in Gaul after about 500 BCE. Initially the Romans, who had not forgotten the capture of their city by Brennus, the leader of Celtic war bands, about 390 BCE, despised and feared the Celts as barbarian savages. Until the end of the 1st century BCE, they disparaged Gaul beyond the Province as Gallia Comata ("Long-Haired Gaul"), mocked and exploited the Gauls' craving for wine, and generally mismanaged the Province itself.

Gaul by then, however, was not far behind Rome in its evolution. In the south, Ligurian communities had long emulated the Hellenic culture of Massilia, as may be seen in the settlement of Entremont (near Aquae Sextiae [Aix-en-Provence]). In the Celtic core, Caesar found large nations (his civitates) coalescing out of smaller tribes (pagi) and establishing urban centres (oppida—e.g., Bibracte [Mont Beuvray], near Augustodunum [Autun]), which, though quite unlike the Classical city-states, were assuming significant economic and administrative functions. After the corrupt Roman Republic was replaced by the empire and its more prudent rule, these advances in Transalpine Gaul could be exploited for the imperial good. The Province, now Narbonensis, was planted with settlements of retired Roman soldiers (coloniae, "colonies"—e.g., Arelate [Arles]); it soon became a land of city-states and was comparable to Italy in its way of life. In the remaining "three Gauls"—Lugdunensis, Aquitania, and Belgica—such colonies were few; there the civitates were retained, as was the habit of fierce rivalry between their leaders. Competition, however, was diverted from war: status was now measured in terms of the level of Romanization attained by both the individual and his community.

Northern Gaul therefore became a Romanized land too. This is dramatically reflected in the dominance of Latin as the language of education and government; French was to be a Romance tongue. Archaeologically, however, Romanization in Gaul is most evident in the emergence of the Greco-Roman city. Although the civitates were too large to act as true city-states, they contained towns, either already in existence (e.g., Lutetia Parisiorum [Paris]) or newly founded (e.g., Augustodunum ["Augustusville"]), that could be designated as their administrative centres and developed, by local magnates at their own expense, in accordance with Classical criteria. Thus, these civitas-capitals, as scholars term them, were characterized by checkerboard street grids and imposing administrative and recreational buildings such as forums, baths, and amphitheatres. Although they display vernacular architectural traits, they essentially follow the best Mediterranean fashion. Most were unwalled—an indicator of the Pax Romana, a tranquil period of about 150 years.

The mark of Rome is also discernible in the countryside, in the shape of villas. Villas of this period were, however, working farms as much as Romanized country residences—manor houses, not palaces. The survivors of the great Gallic aristocracy of the pre-Roman period, who first adopted Roman ways and who might eventually have constructed rural palaces, persisted into the 1st century CE but then seem to have been eclipsed by lesser landowners.

Scholars dispute the extent to which the mass of the Gallic population (about 10 million, or 15 persons per square kilometre [39 persons per square mile], large for a preindustrial economy), free or slave, benefited from the new conditions, but there is no doubt that the landowners prospered. One of the great engines of their wealth was the Rhine army, which stimulated trade by purchasing its supplies from the interior. Commerce was greatly facilitated by a road network and system of river transport that had been expanded and improved under Roman administration. It is no accident that the capital of high imperial Gaul was Lugdunum (Lyon), the main Gallic road junction and a great inland port on the river route that led north to Colonia Agrippinensis (Cologne), the chief city of the two German provinces.

It is not surprising, therefore, that there was relatively little resistance to Roman rule and that Vercingetorix's rebellion was ultimately unsuccessful. There were localized revolts in 21 CE and 69–70, but these were easily suppressed. They may have accelerated the demise of the old Gallic aristocracy; few Gauls subsequently pursued imperial Roman careers (for example, as senators). This diffidence, perhaps initially due to lingering Roman prejudice against Celts but reinforced by Gallic contentment with local responsibilities, may have served to keep Gallic wealth in Gaul.

Gaul under the late Roman Empire (c. 250–c. 400)

High Roman Gaul came to an end in an empirewide crisis characterized by foreign invasions and a rapid succession of rulers, as increased pressure on the empire's frontiers exacerbated its internal economic and political weaknesses. Priority was given to holding the Danube and the East; despite sporadic visits by emperors, the West was neglected. In 260 and 276 Gaul suffered depredation by two recent confederations of Germanic peoples, the Alemanni and the Franks (facing Upper and Lower Germany, respectively). The ensuing civil war left Gaul, Britain, and (for a while) Spain governed by a line of "Gallic" emperors (beginning with Postumus [reigned 260–268]). These lands were reconquered by the Roman emperor Aurelian in 274, though there was further revolt about 279–80. Although unity was reestablished and order of a sort restored by Aurelian (reigned 270–275), Probus (276–282), and Carinus (283–285), the country was much altered. For example, about 260 the Agri Decumates were abandoned, and, from about the reign of Probus, there began an extensive program of city fortification, though on very restricted circuits that cut through, and even used as building material, the proud structures of the previous age. The countryside was prey to marauding peasants. There was, however, no move to exploit the crisis to gain independence: the "Gallic Empire," though closely involving leading Gallic civilians, depended on the loyalty of the Rhine army; it thus championed Gallo-Roman, not Gallic, interests (essentially, the maintenance of a strong Rhine frontier).

After Diocletian and his successors radically reformed the empire in the late 3rd and early 4th centuries, Gaul enjoyed a new stability and even an enhanced role in imperial life. The reason for this was the empire's renewed commitment to defend Italy from the Rhine. To ensure the loyalty of the Rhine garrison and the civil population that depended on it for protection, imperial representation in the frontier region became permanent. An official of the highest rank, a praetorian prefect, was based there, and a series of emperors and usurpers (in particular, Constantine I [reigned 306–337], Julian [355–363], Valentinian I> [364–375], Gratian [375–383], and Magnus Maximus [383–388]) resided there for at least part of their reigns. Their seat of government was usually Augusta Treverorum (now Trier, Germany), the former civitas-capital of the Treveri and capital of Belgica, now "the Rome of the West." (An interesting exception to the rule was Julian, who, with Trier rendered inhospitable by war, wintered in Paris, giving that city its first taste of future greatness.) Throughout the 4th century and especially in its latter half, the ever-present German menace as well as internecine strife occasionally caused the Rhine frontier to be broken, but it was always vigorously restored.

Some recovery of economic prosperity occurred, though it was fragile and uneven. The levying of taxes in kind rather than in cash may have weakened commerce, and the settlement of captive barbarians on the land indicates a rural labour shortage. Trier was endowed with magnificent buildings, but most Gallic cities failed to recover their Classical grandeur. The well-to-do, who were for the most part probably not descended from the aristocracy of high Roman Gaul (destroyed in the 3rd-century crisis), had loftier ambitions than their predecessors. Looking beyond the civitates, they eagerly sought posts in the imperial administration, now conveniently close at hand, basing their claim to advancement on their learning. (Gallo-Roman education, drawing vitality from the Gallo-Celtic love of eloquence, had long been renowned, but it blossomed fully in the 4th century in famous universities such as the one at Burdigala [Bordeaux].) As the century progressed, some educated Gauls grew extremely powerful; the best-known, Ausonius (c.310–c. 393), a poet and professor at Burdigala, was appointed tutor of the future emperor Gratian and became his counselor. These worldly aristocrats, when not at court, favoured the country life; the latter 4th century saw the rise of the palatial villa, especially in the southeast. Other Gauls looked to serve an even higher power; Christianity, thought to have been introduced in the region about 250 by St. Denis of Paris, took root deeply in the land in the century following. An episcopal hierarchy(based on the Roman provinces and civitates) was developed, and monasticism was introduced by Martin of Tours (c. 316–397).

The end of Roman Gaul (c. 400–c. 500)

From 395 the division of the Roman Empire into an eastern and a western half reinforced acute internal political stresses that encouraged barbarian penetration of the Danube region and even Italy. The Rhine frontier was again neglected, and the seat of the Gallic prefecture was moved to Arelate. The result was Germanic invasion, most dramatically the mass crossing of the Rhine in 405–406, and civil war. By 418, Franks and Burgundians were established west of the Rhine, and the Visigoths settled in Aquitania (Aquitaine). These Germans, however, were nominally allies of the empire, and, mainly because of the energy of the Roman general Flavius Aetius, they were kept in check. The death of Aetius in 454 and the growing debility of a western imperial government hamstrung by the loss of Africa to the Vandals created a power vacuum in Gaul. It was filled by the Visigoths, at first indirectly through the nomination of the emperor Avitus (reigned 455–456) and then directly by their own kings, the most important being King Euric (466–484). Between 460 and 480 there was steady Visigothic encroachment on Roman territory to the east; the Burgundians followed suit, expanding westward from Sapaudia (now Savoy). In 476 the last imperial possessions in Provence were formally ceded to the Visigoths.

Gaul suffered badly from these developments. Communities near the Rhine were destroyed by war. Refugees fled south, to Roman territory, only to find themselves burdened by crippling taxation and administrative corruption. As is evident from the works of the writer Sidonius Apollinaris (c. 430–c. 490), however, the economic power and with it the lifestyle of the Gallo-Roman aristocracy remained remarkably resilient, whether under Roman emperors or barbarian kings. Many aristocrats, such as, for example, Sidonius himself, also confirmed their standing in their communities by becoming bishops. Until the middle of the 5th century, the leaders of Gallic society, lay and clerical, while learning to live with the barbarian newcomers, still looked to Rome for high office and protection. Thereafter they increasingly cooperated with the German rulers as generals and counselors. Thus, at least in the centre and south of the country, the Gallo-Roman cultural legacy was bequeathed intact to the successor-kingdoms.

Merovingian and Carolingian age

The period of the Merovingian and Carolingian Frankish dynasties (450–987) encompasses the early Middle Ages. After the 4th and 5th centuries, when Germanic peoples entered the Roman Empire in substantial numbers and brought the existence of that Mediterranean state to an end, the Franks played a key role in Gaul, unifying it under their rule. Merovingian and, later, Carolingian monarchs created a polity centred in an area between the Loire and Rhine rivers but extending beyond the Rhine into large areas of Germany.

Origins

Early Frankish period

In the second quarter of the 5th century, various groups of Franks moved southward. The Ripuarian Franks, as they would be known, settled in the middle Rhine area (near Cologne) and along the lower branches of the Moselle and Meuse rivers, and the Salian Franks, as they came to be known, found homes in the Atlantic coastal region. In the latter area, separate groups took possession of Tournai and Cambrai and reached the Somme River. These Franks along the coast were divided into many small kingdoms. One of the better-known groups established itself in and around the city (urbs) of Tournai; its kinglet (regulus) was Childeric (died c. 481/482), who traditionally is regarded as a close relative in the male line of Merovech, eponymous ancestor of the Merovingian dynasty and descendant of a sea god. Childeric placed himself in the service of the Roman Empire.

Gaul and Germany at the end of the 5th century

Preceding the arrival of the Franks, other Germans had already entered Gaul. The area south of the Loire was divided between two groups. One, the Visigoths, occupied Aquitaine, Provence, and most of Spain. Their king, Euric (reigned 466–484), was the most powerful monarch in the West. The other group, the Burgundians, ruled much of the Rhône valley. In northern Gaul the Alemanni occupied Alsace and moved westward into the area between the Franks and Burgundians, while the first British immigrants established themselves on the Armorican peninsula (now Brittany). Substantial parts of Gaul were ruled by Syagrius, a Roman king (rex) with his capital at Soissons.

In spite of the influx of Germans, whose numbers have been exaggerated, Gaul, which had been part of the Roman Empire for about 500 years, remained thoroughly Romanized. Because many of its administrative institutions withstood the crisis of the 5th century, Gaul's traditional Roman civilization survived, at least in attenuated form, especially among the aristocratic classes. The core of political, social, economic, and religious life remained in the civitas with the urbs at its heart. In addition, the Germans themselves were, to varying degrees, Romanized. This influence was stronger among the Burgundians and the Visigoths, who had lived within the empire for a longer time and had intermingled with other Germanic peoples to a great extent, than it was among the Franks and Alemanni, who had only recently entered the empire even though they had fought alongside or against Rome since the 3rd century. On the other hand, the Burgundians and Visigoths were often seen in an unfavourable light by the Romans because they adopted a heretical form of Christianity—Arianism. The Franks and Alemanni, who preserved limited contacts with Germans living outside the boundaries of the Roman Empire, remained pagan, which the Romans viewed less harshly than heresy.

In effect, the Germanic peoples who penetrated into Roman Gaul were but a small segment of the Germanic world. The northern Germans (Angles, Jutes, Saxons, and Frisians) still occupied the coastal regions of the North Sea east of the Rhine, and the Thuringians and Bavarians divided the territory between the Elbe and Danube. The Slavic world began on the opposite bank of the Elbe.

The Merovingians

Clovis and the unification of Gaul

Frankish expansion

French educational card, late 19th/early 20th century.

Clovis (reigned 481/482–511), the son of Childeric, unified Gaul with the exception of areas in the southeast. According to the traditional and highly stylized account by Gregory of Tours that is now generally questioned by scholars in its particulars, Clovis consolidated the position of the Franks in northern Gaul during the years following his accession. In 486 he defeated Syagrius, the last Roman ruler in Gaul, and in a series of subsequent campaigns with strong Gallo-Roman support he occupied an area situated between the Frankish kingdom of Tournai, the Visigothic and Burgundian kingdoms, and the lands occupied by the Ripuarian Franks and the Alemanni, removing it from imperial control once more. It was probably during this same period that he eliminated the other Salian kings. In a second phase he attacked the other Germanic peoples living in Gaul, with varying degrees of success. An Alemannian westward push was blocked, probably as a result of two campaigns—one conducted by the Franks of the kingdom of Cologne about 495–496 at the Battle of Tolbiacum (Zülpich), the second by Clovis about 506, after his annexation of Cologne. Clovis thus extended his authority over most of the territory of the Alemanni. Some of the former inhabitants sought refuge in the Ostrogothic kingdom of Theodoric the Great, the most powerful ruler in the West at that time.

In the late 490s, according to the traditional chronology, Clovis absorbed the region between the Seine and the Loire (including Nantes, Rennes, and Vannes) and then moved against the Visigothic kingdom. He defeated Alaric II at Vouillé (507). He annexed Aquitaine, between the Loire, Rhône, and Garonne, as well as Novempopulana, between the Garonne and the Pyrenees. Opposed to a Frankish hegemony in the West, Theodoric intervened on behalf of the Visigothic king. He prevented Clovis from annexing Septimania, on the Mediterranean between the Rhône and the Pyrenees, which the Visigoths retained, and occupied Provence. In addition, Clovis eliminated various Frankish kinglets in the east and united the Frankish people under his own leadership.

Clovis established Paris as the capital of his new kingdom, and in 508 he received some sort of recognition from Emperor Anastasius, possibly an honorary consulship, and the right to use the imperial insignia. These privileges gave the new king legitimacy of sorts and were useful in gaining the support of his Gallo-Roman subjects.

The conversion of Clovis

According to Gregory of Tours, Clovis came to believe that his victory at Tolbiacum in 496 was due to the help of the Christian God, whom his wife Clotilda had been encouraging him to accept. With the support of Bishop Remigius of Reims, a leader of the Gallo-Roman aristocracy, Clovis converted to Catholic Christianity with some 3,000 of his army in 498. This traditional account of the conversion, however, has been questioned by scholars, especially because of the echoes of the conversion of Constantine that Gregory so clearly incorporated in his history. Scholars now believe that Clovis did not convert until as late as 508 and did not convert directly from paganism to Catholic Christianity but accepted Arian Christianity first. Clovis did, however, convert to the Catholic faith, and this conversion assured the Frankish king of the support not only of the ecclesiastical hierarchy but also of Roman Catholic Christians in general—the majority of the population. It also ensured the triumph in Gaul of Roman Christianity over paganism and Arianism and spared Gaul the lengthy conflicts that occurred in other Germanic kingdoms.

The sons of Clovis

Following the death of Clovis in 511, the kingdom was divided among his four sons. This partition was not made according to ethnic, geographic, or administrative divisions. The only factor taken into account was that the portions be of equal value. This was defined in terms of the royal fisc (treasury), which had previously been the imperial fisc, and tax revenues from land and trade, which were based upon imperial practices. Boundaries for the division were poorly defined.

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Clovis's lands included two general areas: one was the territory north of the Loire River (the part of Gaul that was conquered earliest); the other, to the south, in Aquitaine, was a region not yet assimilated. Theodoric I, Clovis's eldest son by one of the wives he married in Germanic style before Clovis married Clotilda and converted to Christianity, received lands around the Rhine, Moselle, and upper Meuse rivers, as well as the Massif Central. Clodomir was given the Loire country to the other side of the Rhine, which was the only kingdom not composed of separated territories. Childebert I inherited the country of the English Channel and the lower Seine and, probably, the region of Bordeaux and Saintes. Chlotar I was granted the old Frankish country north of the Somme and an ill-defined area in Aquitaine. Their capitals were centred in the Paris Basin, which was divided among the four brothers: Theodoric used Reims; Clodomir, Orléans; Childebert, Paris; Chlotar, Soissons. As each brother died, the survivors partitioned the newly available lands among themselves. This system resulted in bloody competition until 558, when Chlotar, after his brothers' deaths, succeeded in reuniting the kingdom under his own rule.

The conquest of Burgundy

In spite of these partitions, the Frankish kings continued their conquests. One of their primary concerns was to extend their dominion over the whole of Gaul. It took two campaigns to overcome the Burgundian kingdom. In 523 Clodomir, Childebert I, and Chlotar I, as allies of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths, moved into Burgundy, whose king, Sigismund, Theodoric's son-in-law, had assassinated his own son. Sigismund was captured and killed. Godomer, the new Burgundian king, defeated the Franks at Vézeronce and forced them to retreat; Clodomir was killed in the battle. Childebert I, Chlotar I, and Theodebert I, the son of Theodoric I, regained the offensive in 532–534. The Burgundian kingdom was annexed and divided between the Frankish kings. Following Theodoric the Great's death in 526, the Franks were able to gain a foothold in Provence by taking advantage of the weakened Ostrogothic kingdom. The Franks were thus masters of all of southeastern Gaul and had reached the Mediterranean. But, in spite of two expeditions (531 and 542), they were unable to gain possession of Visigothic Septimania. Also, at least a portion of Armorica in the northwest remained outside the Frankish sphere of influence. During this period, British colonization of the western half of the Armorican peninsula was at its height.

The conquest of southern Germany

To the east, the Franks extended their domain in southern Germany, subjugating Thuringia (about 531 Chlotar I carried off Radegunda, a niece of the Thuringian king), the part of Alemannia between the Neckar River and the upper Danube (after 536), and Bavaria. The latter was created as a dependent duchy about 555. The Franks were less successful in northern Germany; in 536 they imposed a tribute on the Saxons (who occupied the area between the Elbe, the North Sea, and the Ems), but the latter revolted successfully in 555.

Theodebert I and his son, Theodebald, sent expeditions into Italy during a struggle between the Ostrogoths and Byzantines (535–554), but they achieved no lasting results.

The grandsons of Clovis

At the death of Chlotar I (561), the Frankish kingdom, which had become the most powerful state in the West, was once again divided, this time between his four sons. The partition agreement was based on that of 511 but dealt with more extensive territories. Guntram received the eastern part of the former kingdom of Orléans, enlarged by the addition of Burgundy. Charibert I's share was fashioned from the old kingdom of Paris (Seine and English Channel districts), augmented in the south by the western section of the old kingdom of Orléans (lower Loire valley) and the Aquitaine Basin. Sigebert I received the kingdom of Reims, extended to include the new German conquests; a portion of the Massif Central (Auvergne) and the Provençal territory (Marseille) were added to his share. Chilperic I's portion was reduced to the kingdom of Soissons.

The death of Charibert (567) resulted in further partition. Chilperic, the principal beneficiary, received the lower Seine district, including a large tract of the English Channel coast. The remainder, most notably Aquitaine and the area around Bayeux, was divided in a complex manner; and Paris was subject to joint possession. The partitions of 561 and 567, which reaffirmed the division of Francia, were the sources of innumerable intrigues and family struggles, especially between, on the one hand, Chilperic I, his wife the former slave Fredegund, and their children, who controlled northwestern Francia, and, on the other hand, Sigebert I, his wife the Visigothic princess Brunhild, and their descendants, the masters of northeastern Francia.

The shrinking of the frontiers and peripheral areas

These events undermined the Frankish hegemony. In Brittany the Franks maintained control of the eastern region but had to cope with raids by the Bretons, who had established heavily populated settlements in the western part of the peninsula. To the southwest the Gascons, a highland people from the Pyrenees, had been driven northward by the Visigoths in 578 and settled in Novempopulana; in spite of several Frankish expeditions, this area was not subdued. In the south the Franks were unable to gain control of Septimania; they tried to accomplish this by means of diplomatic agreements, which were buttressed by dynastic intermarriage, and by military campaigns occasioned by religious differences (the Visigothic kings were Arians). In the southeast the Lombards, who had recently arrived in Italy, made several raids on Gaul(569, 571, 574); Frankish expeditions into Italy (584, 585, 588, 590), led by Childebert II, were without result. Meanwhile the Avars, a people of undetermined origin who settled along the Danube in the second half of the 6th century, threatened the eastern frontier; in 568 they took Sigebert prisoner, and in 596 they attacked Thuringia, forcing Brunhild to purchase their departure.

The parceling of the kingdom

Internal struggles resulted in the emergence of new political configurations. At the time of the partitions of 561 and 567, new political-geographic units began to appear within Gaul. Austrasia was created from the Rhine, Moselle, and Meuse districts, which had formerly been the kingdom of Reims, and from the areas east of the Rhône conquered by Theodoric I and his son Theodebert; Sigebert I (died 575) transferred the capital to Metz to take advantage of the income provided by trade on the Rhine. Neustria was born out of the partition of the kingdom of Soissons; a portion of the kingdom of Paris was added to it, thus endowing the area with a broad coastal section and making the lower Seine valley its centre. Its first capital, Soissons, was returned to Austrasia following the death of Chilperic I; its capital was later moved to Paris, which had been controlled by Chilperic. The kingdom of Orléans, without its western territory but with part of the old Burgundian lands added to it, eventually became Burgundy; Guntram fixed its capital at Chalon-sur-Saône. Aquitaine submitted to the Frankish kingdoms centred farther north in Gaul; its civitates were the object of numerous partitions made by sovereigns who regarded it as an area for exploitation. Aquitaine did not enjoy political autonomy during this period.

The failure of reunification (613–714)

Chlotar II and Dagobert I

Territorial crisis was partially and provisionally averted during the first third of the 7th century. Chlotar II, son of Chilperic I and Fredegund and king of Neustria since 584, took control of Burgundy and Austrasia in 613 upon the brutal execution of Brunhild, and thus a united kingdom once again was created. He fixed his capital at Paris and, in 614, convoked a council there, at which he recognized the traditional prerogatives of the aristocracy (Gallo-Roman and Germanic) in order to gain their support in the governing of the kingdom. His son Dagobert I (reigned 629–639) was able to preserve this unity. He journeyed to Burgundy, where the highest political office, mayor of the palace, was maintained; to Austrasia; and then to Aquitaine, which was given the status of a duchy. He thus recognized structures of imperial origin.

Dagobert had only limited success along the frontier. In 638 he placed the Bretons and the Gascons under nominal subjection, but ties with these peripheral peoples were tenuous. He intervened in dynastic quarrels of Spain, entering the country and going as far as Zaragoza before receiving tribute and quitting. Septimania remained Visigothic. On the eastern frontier there were incidents involving Frankish merchants and Moravian and Czech Slavs; after the failure of a campaign conducted by Dagobert, with the assistance of the Lombards and Bavarians (633), the Slavs attacked Thuringia. The king reached an agreement with the Saxons, who would protect the eastern frontier in return for remission of a tribute they had paid since 536. Thus, Dagobert used traditional imperial techniques to protect the frontiers with more or less Romanized barbarians.

The hegemony of Neustria

The territorial struggles began anew after 639. In Neustria, Austrasia, and Burgundy, power was gradually absorbed by aristocratic leaders, particularly the mayors of the palace. Ebroïn, mayor of the palace in Neustria, attempted to unify the kingdom under his leadership but met with violent opposition. Resistance in Burgundy was led by Bishop Leodegar, who was assassinated about 679 (he was later canonized). Austrasia was governed by the Pippinid mayors of the palace, who were given the office as a reward for their founder's support of Chlotar in the overthrow of Brunhild; Pippin I of Landen was succeeded by his son Grimoald, who tried unsuccessfully to have his son, Childebert the Adopted, crowned king, and by Pippin II of Herstal (or Héristal), whom Ebroïn was briefly able to keep from power (c. 680).

Frankish hegemony was once more threatened in the peripheral areas, especially to the east where Austrasia was endangered. The Thuringians (640–641) and Alemanni regained their independence. The Frisians reached the mouth of the Schelde River and controlled the towns of Utrecht and Dorestat; the attempted conversion of Frisia by Wilfrid of Northumbria had to be abandoned (c. 680). In southern Gaul the duke Lupus changed the status of Aquitaine from a duchy to an independent principality.

Austrasian hegemony and the rise of the Pippinids

The murder of Ebroïn (680 or 683) reversed the situation in favour of Austrasia and the Pippinids. Pippin II defeated the Neustrians at Tertry in 687 and reunified northern Francia under his own control during the next decade. Austrasia and Neustria were reunited under a series of Merovingian kings, who retained much traditional power and authority while Pippin II consolidated his position as mayor of the palace. At the same time, Pippin II partially restabilized the frontiers of northern Francia by driving the Frisians north of the Rhine and by restoring Frankish suzerainty over the Alemanni. But control of southern Gaul continued to elude Pippin II and his supporters. In the early 8th century, Provence became an autonomous duchy, while power in Burgundy was divided.

The Carolingians

Representatives of the Merovingian dynasty continued to hold the royal title until 751. Chroniclers in the service of their successors, the Carolingians—as the Pippinids would come to be known—stigmatized the Merovingians as "do-nothing kings." Although some of the later Merovingian kings inherited the title as children and died young, they retained at least some power into the 8th century, and only in the 720s did they become mere puppets. At the same time, however, effective power was increasingly concentrated in the hands of the Pippinids, who, thanks to their valuable landholdings and loyal retainers, maintained a monopoly on the office of mayor of the palace. Because of their familial predisposition for the name Charles and because of the significance of Charlemagne in the family's history, modern historians have called them the Carolingian dynasty.

Charles Martel and Pippin III

Pippin II's death in 714 jeopardized Carolingian hegemony. His heir was a grandchild entrusted to the regency of his widow, Plectrude. There was a revolt in Neustria, and Eudes, duc d'Aquitaine, used the occasion to increase his holdings and make an alliance with the Neustrians. The Saxons crossed the Rhine, and the Arabs crossed the Pyrenees.

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Charles Martel

The situation was rectified by Pippin's illegitimate son, Charles Martel. Defeating the Neustrians at Amblève (716), Vincy (717), and Soissons (719), he made himself master of northern Francia. He then reestablished Frankish authority in southern Gaul, where the local authorities could not cope with the Islamic threat; he stopped the Muslims near Poitiers(Battle of Tours; 732) and used this opportunity to subdue Aquitaine(735–736). The Muslims then turned toward Provence, and Charles Martel sent several expeditions against them. At the same time, he succeeded in reestablishing authority over the dissident provinces in the southeast (737–738) with the exception of Septimania. Finally, he reestablished his influence in Germany. In his numerous military campaigns he succeeded in driving the Saxons across the Rhine, returned the Bavarians to Frankish suzerainty, and annexed southern Frisia and Alemannia. He also encouraged missionary activity, seeing it as a means to consolidate his power. Most notably, Charles supported the Anglo-Saxon missionaries, especially Winfrith (the future St. Boniface), who spread the faith east of the Rhine. The work of the Anglo-Saxons was sanctioned by the papacy, which was beginning to seek support in the West at the same time that St. Peter's prominence was growing among the Franks. Moreover, long-lasting ties with England brought Boniface to Rome for papal blessing of missionary work, and his activities strengthened ties between the pope and the Franks.

Charles Martel had supported a figurehead Merovingian king, Theodoric IV (reigned 721–737), but upon the latter's death he felt his own position secure enough to leave the throne vacant. His chief source of power was a strong circle of followers who furnished the main body of his troops and became the most important element in the army because local dislocation of government had weakened the recruitment of the traditional levies of freemen. He attached them to himself by concessions of land, which he obtained by drawing on the considerable holdings of the church. This gave him large tracts of land at his disposal, which he granted for life (precaria). He was thus able to recruit a larger and more powerful circle of followers than that surrounding any of the other influential magnates.

Pippin III

At the death of Charles Martel (741), the lands and powers in his hands were divided between his two sons, Carloman and Pippin III (the Short), as was the custom. This partition was followed by unsuccessful insurrections in the peripheral duchies—Aquitaine, Alemannia, and Bavaria. The seriousness of these revolts, however, encouraged Pippin and Carloman to place the Merovingian Childeric III, whom they conveniently discovered in a monastery, on the throne in 743.

Carloman's entrance into a monastery in 747 reunited Carolingian holdings. Pippin the Short, who as mayor of the palace had held de facto power over Francia, or the regnum Francorum ("kingdom of the Franks"), now desired to be king. He was crowned with the support of the papacy, which, threatened by the Lombards and having problems with Byzantium, sought a protector in the West. To accomplish this goal, he sent a letter to Pope Zacharias in 750 asking whether he who had the power or the title should be king, and he received the answer he desired. In 751 Pippin deposed Childeric III; he then had himself elected king by an assembly of magnates and consecrated by the bishops, thus ending the nominal authority of the last Merovingian king. The new pope, Stephen II (or III), sought aid from Francia; in 754 at Ponthion he gave Pippin the title Patrician of the Romans, renewed the king's consecration, and consecrated Pippin's sons, Charles and Carloman, thus providing generational legitimacy for the line.

As king, Pippin limited himself to consolidating royal control in Gaul, thus establishing the base for later Carolingian expansion. Despite Pippin's efforts, the situation at the German frontier was unstable. The duchy of Bavaria, which had been given to Tassilo III as a benefice, gained its independence in 763; several expeditions were unable to subdue the Saxons. On the other hand, Pippin achieved a decisive victory in southern Gaul by capturing Septimania from the Muslims (752–759). He broke down Aquitaine's resistance, and it was reincorporated into the kingdom (760–768). Pippin campaigned in Italy against the Lombards twice (754–755; 756) on the appeal of the pope and laid the foundations for the Papal States with the so-called Donation of Pippin. He exchanged ambassadors with the great powers of the eastern Mediterranean—the Byzantine Empire and the Caliphate of Baghdad. He also continued a program of reform of the church and religious life that he had begun with Carloman.

Charlemagne

Pippin III was faithful to ancient customs, and upon his death in 768 his kingdom was divided between his two sons, Charles (Charlemagne) and Carloman. The succession did not proceed smoothly, however, as Charlemagne faced a serious revolt in Aquitaine as well as the enmity of his brother, who refused to help suppress the revolt. Carloman's death in 771 saved the kingdom from civil war. Charlemagne dispossessed his nephews from their inheritance and reunited the kingdom under his own authority.

The conquests

Charlemagne consolidated his authority up to the geographic limits of Gaul. Though he put down a new insurrection in Aquitaine (769), he was unable to bring the Gascons and the Bretons fully under submission. However, Charlemagne extended considerably the territory he controlled and unified a large part of the Christian West. He followed no grand strategy of expansion, instead taking advantage of situations as they arose.

He pursued an active policy toward the Mediterranean world. In Spain he attempted to take advantage of the emir of Córdoba's difficulties; he was unsuccessful in western Spain, but in the east he was able to establish a march, or border territory, south of the Pyrenees to the important city Barcelona. Pursuing Pippin's Italian policy, he intervened in Italy. At the request of Pope Adrian I, whose territories had been threatened by the Lombards, he took possession of their capital city, Pavia, and had himself crowned king of the Lombards. In 774 he fulfilled Pippin's promise and created a papal state; the situation on the peninsula remained unsettled, however, and many expeditions were necessary. This enlargement of his Mediterranean holdings led Charlemagne to establish a protectorate over the Balearic Islands in the western Mediterranean (798–799).

Charlemagne conquered more German territory and secured the eastern frontier. By means of military campaigns and missionary activities he brought Saxony and northern Frisia under control; the Saxons, led by Widukind, offered a protracted resistance (772–804), and Charlemagne either destroyed or forcibly deported a large part of the population. To the south, Bavaria was brought under Frankish authority and annexed. Conquests in the east brought the Carolingians into contact with new peoples—Charlemagne was able to defeat the Avars in three campaigns (791, 795, 796), from which he obtained considerable booty; he was also able to establish a march on the middle Danube, and the Carolingians undertook the conversion and colonization of that area. Charlemagne established the Elbe as a frontier against the northern Slavs. The Danes constructed a great fortification, the Danewirk, across the peninsula to stop Carolingian expansion. Charlemagne also founded Hamburg on the banks of the Elbe. These actions gave the Franks a broad face on the North Sea.

The Frankish state was now the principal power in the West. Charlemagne claimed to be defender of Roman Christianity and intervened in the religious affairs of Spain. Problems arose over doctrinal matters that, along with questions concerning the Italian border and the use of the imperial title, brought him into conflict with the Byzantine Empire; a peace treaty was signed in 810–812. Charlemagne continued his peace policy toward the Muslim East: ambassadors were exchanged with the caliph of Baghdad, and Charlemagne received a kind of eminent right in Jerusalem.

The restoration of the empire

When by the end of the 8th century Charlemagne was master of a great part of the West, he reestablished the empire in his own name. He was crowned emperor in Rome on Christmas Day, 800, by Pope Leo III, who had been savagely attacked by rivals in Rome in 799 and who hoped that the restoration of an imperial authority in western Europe would protect the papacy. Charlemagne's powers in Rome and in relation to the Papal States, which were incorporated, with some degree of autonomy, into the Frankish empire, were clarified. Although his new title did not replace his royal titles, it was well suited to his preponderant position in the old Roman West. The imperial title, later known as Holy Roman emperor, indicates a will to unify the West; nevertheless, in his succession plan of 806, Charlemagne preserved the kingdom of Italy, giving the crown to one of his sons, Pippin, and made Aquitaine a kingdom for his other son, Louis. The continuing dispute with the Byzantines over the imperial title may have led to his reluctance to pass it on, or, more likely, he saw it as a personal honour in recognition of his great achievements.

Louis I

Only chance ensured that the empire remained united under Louis I (the Pious), the last surviving son of Charlemagne. Louis was crowned emperor in 813 by his father, who died the following year. The era of great conquests had ended, and, on the face of it, Louis's principal preoccupation was his relationship with the peoples to the north. In the hope of averting the threat posed by the Vikings, who had begun to raid the coasts of the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, Louis proposed to evangelize the Scandinavian world. This mission was given to St. Ansgar but was a failure.

During Louis's reign, the imperial bureaucracy was given greater uniformity. Louis the Pious saw the empire, above all, as a religious ideal, and in 816 in a separate ceremony the pope anointed him and crowned him emperor. At the same time, Louis took steps to regulate the succession so as to maintain the unity of the empire (Ordinatio Imperii, 817). His eldest son, Lothar I, was to be sole heir to the empire, but within it three dependent kingdoms were maintained: Louis's younger sons, Pippin and Louis, received Aquitaine and Bavaria, respectively; his nephew Bernard was given Italy. He also replaced the dynasty's customary relationship with the pope with the Pactum Hludowicianum in 817, which clearly defined relations between the two in a way that favoured the emperor.

The remarriage of Louis the Pious to Judith of Bavaria and the birth of a fourth son, who would rule as Charles II (the Bald), upset this project. In spite of opposition from Lothar, who had the support of a unity faction drawn from the ranks of the clergy, the emperor sought to create a kingdom for Charles the Bald. These divergent interests would undermine Louis's authority and cause much civil strife. Notably, in 830 Louis faced a revolt by his three older sons, and in 833–834 he confronted a second, more serious revolt. In 833 he was abandoned by his followers on the Field of Lies at Colmar and then deposed and forced by Lothar to do public penance. Judith and Charles were placed in monasteries. Lothar, however, overplayed his hand and alienated his brothers, who restored their father to the throne. Lothar lived in disgrace until a final reconciliation with his father near the end of Louis's life.

The partitioning of the Carolingian empire

The Treaty of Verdun

After the death of Louis the Pious (840), his surviving sons continued their plotting to alter the succession. Louis II (the German) and Charles II (the Bald) affirmed their alliance against Lothar I with the Oath of Strasbourg (842). After several battles, including the bloody one at Fontenoy, the three brothers came to an agreement in the Treaty of Verdun (843). The empire was divided into three kingdoms arranged along a north-south axis: Francia Orientalis was given to Louis the German, Francia Media to Lothar, and Francia Occidentalis to Charles the Bald. The three kings were equal among themselves. Lothar kept the imperial title, which had lost much of its universal character, and the imperial capital at Aix-la-Chapelle (now Aachen, Germany).

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

The kingdoms created at Verdun

Until 861 the clerical faction tried to impose a government of fraternity on the descendants of Charlemagne, manifested in the numerous conferences they held, but the competition of the brothers and their supporters undermined clerical efforts.

Francia Media proved to be the least stable of the kingdoms, and the imperial institutions bound to it suffered as a result. In 855 the death of Lothar I was followed by a partition of his kingdom among his three sons: the territory to the north and west of the Alps went to Lothar II (Lotharingia) and to Charles (kingdom of Provence); Louis II received Italyand the imperial title. At the death of Charles of Provence (863), his kingdom was divided between his brothers Lothar II (Rhône region) and Louis II (Provence). After the death of Lothar II in 869, Lotharingia was divided between his two uncles, Louis the German and Charles the Bald. Louis, however, did not gain control of his share until 870. Charles was made master of the Rhône regions of the ancient kingdom of Provence, while Louis turned most of his attention to fighting the Muslims who threatened the peninsula and the papal territories.

In Francia Occidentalis Charles the Bald was occupied with the struggle against the Vikings, who ravaged the countryside along the Scheldt, Seine, and Loire rivers. More often than not, the king was forced to pay for their departure with silver and gold. Aquitaine remained a centre of dissension. For some time (until 864) Pippin II continued to have supporters there, and Charles the Bald attempted to pacify them by installing his sons—first Charles the Child (reigned 855–866) and then Louis II (the Stammerer; 867–877)—on the throne of Aquitaine. The problems in Aquitaine were closely connected to general unrest among the magnates, who wished to keep the regional king under their control. By accumulating countships and creating dynasties, the magnates succeeded in carving out large principalities at the still unstable borders: Robert the Strong and Hugh the Abbot in the west; Eudes, son of Robert the Strong, in this same region and in the area around Paris; Hunfred, Vulgrin, Bernard of Gothia, and Bernard Plantevelue (Hairyfoot), count of Auvergne, in Aquitaine and the border regions; Boso in the southeast; and Baldwin I in Flanders. Nevertheless, Charles the Bald appeared to be the most powerful sovereign in the West, and in 875 Pope John VIII arranged for him to accept the imperial crown. An expedition he organized in Italy on the appeal of the pope failed, and the magnates of Francia Occidentalis rose up. Charles the Bald died on the return trip (877). Charles's son Louis the Stammerer ruled for only two years. At his death in 879 the kingdom was divided between his sons Louis III and Carloman. In the southeast, however, Boso, the count of Vienne, appropriated the royal title to the kingdom of Provence. The imperial throne remained vacant. The death of Louis III (882) permitted the reunification of Francia Occidentalis (except for the kingdom of Provence) under Carloman.

In Francia Orientalis royal control over the aristocracy was maintained. But decentralizing forces, closely bound to regional interests, made themselves felt in the form of revolts led by the sons of Louis the German. He had made arrangements to partition his kingdom in 864, with Bavaria and the East Mark to go to Carloman, Saxony and Franconia to Louis the Younger, and Alemannia (Swabia) to Charles III (the Fat). Although Louis the German managed to gain a portion of Lotharingia in 870, he was unable to prevent Charles the Bald's coronation as emperor (875). When Louis the German died in 876, the partition of his kingdom was confirmed. At the death of Charles the Bald, Louis's son Carloman seized Italy and intended to take the imperial title, but ill health forced him to abandon his plans. Carloman's youngest brother, Charles the Fat, benefited from the circumstances and restored the territorial unity of the empire. The deaths of Carloman (880) and Louis the Younger (882) without heirs allowed Charles the Fat to acquire successively the crown of Italy (880) and the imperial title (881) and to unite Francia Orientalis (882) under his own rule. Finally, at the death of Louis the Stammerer's son Carloman, Charles the Fat was elected king of Francia Occidentalis (885); the magnates had bypassed the last heir of Louis the Stammerer, Charles III (the Simple), in his favour. Charles the Fat avoided involving himself in Italy, in spite of appeals from the pope, and concentrated his attention on coordinating resistance to the Vikings, who had resumed the offensive in the valleys of the Scheldt, Meuse, Rhine, and Seine. He was unsuccessful, however, and in 886 had to purchase the Vikings' departure: they had besieged Paris, which was defended by Count Eudes. The magnates of Francia Orientalis rose up and deposed Charles the Fat in 887.

The Frankish world

Society

Germans and Gallo-Romans

The settlement of Germanic peoples in Roman Gaul brought people from two entirely different backgrounds into contact. Linguistic barriers were quickly overcome, for the Germans adopted Latin. At the same time, German names were preponderant. Although there were religious difficulties in those regions settled by peoples converted to Arianism (Visigoths, Burgundians), Clovis's eventual conversion to Catholic Christianity simplified matters. The Germans who settled in Gaul were able to preserve some of their own judicial institutions, but these were heavily influenced by Roman law. The first sovereigns, under Roman influence, committed the customs of the people to writing, in Latin (Code of Euric, c. 470–480; Salic Law of Clovis, c. 507–511; Law of Gundobad, c. 501–515), and occasionally had summaries of Roman rights drawn up for the Gallo-Roman population (Papian Code of Gundobad; Breviary of Alaric). By the 9th century this principle of legal personality, under which each person was judged according to the law applying to his status group, was replaced by a territorially based legal system. Multiple contacts in daily life produced an original civilization composed of a variety of elements, some of which were inherited from antiquity, some brought by the Germans, and many strongly influenced by Christianity.

Social classes

The collapse of Roman imperial power and the influx of Germans did not destroy the old Roman senatorial and landed aristocracy; the 6th-century kings called on its members to serve in the administration. A sort of military aristocracy had existed among the Germans: at the time of their settlement within the empire, its members were given tax revenues and lands confiscated from the Gallo-Roman aristocracy or awarded from the fisc (royal treasury). The two groups fused rapidly. They shared a common life, discharging public and religious duties and frequenting the court. By the beginning of the 7th century, there arose an aristocracy of office, whose signs of prestige were the possession of land and service to the king and church. This aristocracy increased in importance during the conflicts between the Merovingian sovereigns. The ascendance of the Pippinids, Carolingian rule, and the power struggles in the 9th century furnished these magnates, on whom those in power were dependent, with a means of enriching themselves and augmenting their political and social influence.

Parallel to this class of lay magnates and largely drawn from the same families was an ecclesiastical aristocracy, which was one both of office and of land. The church found itself in possession of a vast landed fortune. At the beginning of the 7th century, at least, the church frequently benefited from immunity, and governmental rights were conferred on abbots or bishops.

A class of small and middle-size landholders apparently existed, about which little is known. It appears that both the power of the magnates and the practices born of the ancient patronage system, combined with extensive military service, had the effect of diminishing the size of this class.

During the Merovingian epoch, slavery, inherited from antiquity, was still a viable institution. Slaves continued to be obtained in war and through trade. But the number of slaves decreased under the influence of the church, which encouraged manumission and sought to prohibit the enslavement of Christians. Under the Carolingians, the slaves in Gaul formed only a residual class, although the slave trade was still active. Taken increasingly from the Slavic territories (the term slavus replaced the traditional servus), slaves were a commodity for trade with the Muslim lands of the Mediterranean.

Diffusion of political power

During the period of insecurity and turbulence that marked the end of the Merovingian epoch, bonds of personal dependence, present in both Roman and Germanic institutions, competed with weakened governmental institutions. In the 7th century these bonds took one of two forms: commendation (a freeman placed himself under the protection of a more powerful lord for the duration of his life) and precarious contract (a powerful lord received certain services in return for the use of his land for a limited time under advantageous conditions). In the 8th century the Pippinids increased their personal circle of followers. Charlemagne sought to establish a personal bond with the entire free population through oaths of loyalty. He encouraged an increase in the number of royal vassals and gave them administrative functions. During the 9th-century power struggles, however, some administrative offices became hereditary, though this represented a distortion of the vassalic relationship. In addition, before the end of the century, a man could place himself in vassalage to several lords. Finally, the usurpation of governmental powers led to the formation of territorial principalities, resulting in a great weakening of royal authority.

Institutions

Kingship

The institutions of government underwent great changes under the Frankish monarchs. Kingship was the basic institution in the Merovingian realm. Since Clovis's reign, the power of the king had extended not only over a tribe or tribes but also over a territory inhabited by Germans of divergent backgrounds and by Gallo-Romans as well. The king exercised power within legal limitations, which, when violated, led to efforts to reestablish political equilibrium by means of civil war, assassination, and an appeal to God and the saints. Royal power was dynastic and patrimonial. The Frankish kings successfully eliminated the Germanic practice of the magnates electing the king (the Frankish king was content to present himself to the magnates who acclaimed him) and accepted the hereditary principle as a personal right. The kings partitioned the kingdom at each succession. Royal power also had a sacred aspect; under the Merovingians the external sign of this was long hair.

The nature of the Frankish monarchy was profoundly changed during the Carolingian epoch. When Pippin III usurped the office of king, he had himself consecrated first by the bishops of his realm (possibly including Boniface) in 751 and then by the pope in 754. This rite, originated by the biblical kings of Israel, had already been adopted by the Visigoths; it gave Christian legitimacy to royal authority because it reinforced the religious character of the monarchy and signified the king's receipt of special grace from God. The king was permitted to reign and was given a stature above that of the common level because of this grace. Acclamation by the magnates became a pledge of obeisance to a king whom God had invested with power.

To this new royal status Charlemagne, who had been called rex et sacerdos (Latin: "king and priest") in the 790s, added the title of emperor, which had not been held by a ruler in the West since 476. Although, according to his biographer, Charlemagne was surprised by the ceremony on Christmas Day in 800, he must surely have known of the coronation. Indeed, during the previous decade his advisers, especially Alcuin, had developed the idea that Charlemagne was a worthy successor to Constantine, the first Christian emperor. Among the clerical ranks that formed the entourage of the new emperor, the revival of the empire was regarded as a magistracy conferred by God in the interests of Western Christianity and the church; imperial authority was considered a kind of priesthood, and its bearer was obligated to lead and protect the faithful. This idea reached fruition under Louis the Pious, who understood his role as that of a Christian emperor and dispensed with the royal designations that his father included in his official title. He also redefined Carolingian relations with the pope, who crowned Louis in 816 and whose role became central in the act of coronation. Later Carolingians were deemed emperors only after coronation by the pope, and, as a result of the divisions of the empire, the emperor's most important duty was defense of the pope.

The central government

By the time of Clovis, the ancient Germanic assembly of freemen participated only in the conduct of local affairs and was consigned largely to a military role. Within each kingdom, the king's court, of Roman imperial origin but adapted and modified by the Frankish sovereigns, encompassed domestic services (treasury, provisioning, stables, clergy), a bureau of accounts, and a military force. The court was presided over by three men—the seneschal, the count of the palace, and, foremost, the mayor of the palace, who also presided over the king's estates. They traveled with the king, who, while having various privileged places of residence, did not live at a fixed capital. Only under Charlemagne did this pattern begin to change; while not abandoning the itinerant life, Charlemagne nonetheless wished to make Aachen the centre of his state. It was there that he constructed a vast palace, which was based upon a late imperial Roman model and of which only the Palatine Chapel remains.

Local institutions

Except in the north, which was divided into districts called pagi (singular pagus), the Merovingians continued to use the city (the Roman civitas) as the principal administrative division. A count, installed in each pagusand city (urbs), delegated financial, military, and judicial authority. Groups of counts were occasionally placed under the authority of a duke, whose responsibilities were primarily military.

The development of institutions in the Carolingian age

The Carolingians contented themselves with refining their administrative system to strengthen royal control and to solve the problems posed by a large empire. The kingdom's cohesion was augmented by an oath of fidelity, which Charlemagne exacted from every freeman (789, 793, 802), and by the publication of legislation—the capitularies—that regulated the administration and exploitation of the kingdom. In the marches, local governments were established.

To improve government further, the episcopate (the body of bishops) was given a central role in the administration, and a new class of judges (scabini) was created. Charlemagne extended the use of the missi dominici—i.e., envoys who also served as liaisons between the central government and local agents and who were responsible for keeping the latter in line. To strengthen his control over the population, Charlemagne attempted to develop intermediary bodies; he tried to use both vassalage and immunity as means of government—in the first instance by creating royal vassals and giving them public offices and in the second by controlling protected institutions such as monasteries and the Jewish community.

Economic life

Agriculture was the principal economic activity, and during the entire Frankish age the great estate, inherited from antiquity, was one of the components of rural life. These estates were, according to contemporary documents known as polyptyques, an important source of income for the aristocracy. The estates appear to have long been placed under cultivation by servile labour, which was abundant at the time. The heavy work was done with the assistance of day labourers. A portion of the land, however, was given to the tenants—the coloni—who were compelled to pay annual charges. With the decline in slavery at the end of the Merovingian era, the number of tenancies increased, and tenants were compelled to render significant amounts of labour to cultivate land held directly by the lord. This bipartite system, in which the lord's "reserve" coexisted with tenant holdings, was not adopted throughout the Frankish empire but became characteristic of the future French heartland between the Loire and the Rhine. Farming techniques were rudimentary and crop yields were low, putting a damper on population growth and economic expansion; during the Merovingian and Carolingian periods, the total population remained below the peak it had reached in Roman times. The Carolingian period, however, especially after 800, witnessed the beginning of climatic and technological change that would lay the foundation for later economic and demographic expansion.

Trade

Despite the Islamic conquests, Mediterranean commerce did not decline abruptly. In Gaul, goods such as papyrus, oil, and spices were imported from the East, and there were numerous colonies of Syrians. Currency continued to be based on the gold standard, and imperial units were still used. All signs, moreover, point to the existence of manufacturing for trade (marble from Aquitaine, Rhenish glass, ceramics). However, in the Carolingian age, Mediterranean trade no longer occupied a primary place in the economy. The adoption of a new monetary system based on silver, along with a reduction in the number of Oriental goods and merchants, are signs of the change. After the 7th century, trade among the countries bordering the English Channel and the North Sea and in the Meuse valley increased steadily. The Scandinavians, with their great commercial centres at Birka in Sweden and Hedeby in Denmark, were both pirates and traders; they established new contacts between East and West.

In addition to this large-scale commerce, there was agriculturally based local trade. The number of markets increased, and market towns began to appear alongside the former Gallo-Roman cities, which survived as fortresses and population centres and served as the basis for religious organization and political administration.

Frankish fiscal law

The Frankish fiscal system reflected the evolution of the economy. Frankish kings were unable to continue the Roman system of direct taxation of land as the basis for their income. Their principal sources of income were the exploitation of the domains of the fisc (royal treasury), war (booty, tribute), the exercise of power (monetary and judicial rights), and the imposition of a growing number of telonea (taxes collected on the circulation and sale of goods).

The church

The episcopate and the diocese were practically the only institutions to survive the collapse of Roman imperial power largely unchanged. Many bishops played important roles in defending the population during the German conquest. During the Frankish era, bishops and abbots occupied a socially prominent position because of both their great prestige among the people and their landed wealth.

Institutions

The organization of the secular church took its final form under the Merovingian and Carolingian kings. The administrative bodies and the hierarchy of the early Christian church were derived from institutions existing during the late Roman Empire. In principle, a bishop was responsible for the clergy and faithful in each district (civitas). The bishop whose seat was in the metropolitan city had preeminence and was archbishop over the other bishops in his archdiocese. The monarchy dominated the church. Kings most often appointed bishops from among their followers without regard for religious qualifications; the metropolitan see was often fragmented in the course of territorial partitions and tended to lose its importance, and the church in Francia increasingly withdrew from papal control despite papal attempts to reestablish ties. The first Carolingians reestablished the ecclesiastical hierarchy. They restored the authority of the archbishops and established cathedral chapters so that the clergy living around a bishop were drawn into a communal life. They also maintained the right to nominate bishops, whom they considered agents of the monarchy.

During the 4th and 5th centuries success at converting the countryside made it necessary for the bishops to divide the dioceses into parish churches. Initially there was a limit of between 15 and 40 of these per diocese. In the Carolingian era they were replaced by small parish churches better suited to the conditions of rural life.

Monasticism

Monasticism originated in the East. It was introduced in the West during the 4th century and was developed in Gaul, mainly in the west (St. Martin of Tours) and southeast (St. Honoratus and St. John Cassian). In the 6th century the number of monasteries throughout Gaul increased, as did the number of rules regulating them. Introduced by St. Columban (c. 543–615), Irish monasticism was influential in the 7th century, but it was later superseded by the Benedictine rule, which originated in Italy. The monasteries suffered from the upheavals affecting the church in the 8th century, and the Carolingians attempted to reform them. Louis the Pious, acting on the advice of St. Benedict of Aniane, imposed the Benedictine rule, which became a characteristic feature of Western monasticism. The Carolingians, however, continued the practice of having lay abbots.

Education

In the 6th century, especially in southern Gaul, the aristocracy and, consequently, the bishops drawn from it preserved an interest in traditional Classical culture. Beginning in the 7th century, the Columbanian monasteries insisted on the study of the Bible and the celebration of the liturgy. In the Carolingian era these innovations shared the focus of education with works of Classical antiquity.

Religious discipline and piety

Characteristic of the church in the 6th century were frequent councils to settle questions of doctrine and discipline. In time, however, the conciliar institution declined, leading to liturgical anarchy and a moral and intellectual crisis among the clergy. Charlemagne and Louis the Pious attempted to impose a uniform liturgy, inspired by the one used at Rome. They also took measures to raise the standard of education of both clerics and the faithful.

The cults of saints and relics were an important part of religion during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Relics, the remains of the holy dead, were thought to have miraculous powers that could convert pagans and cure the sick. Consequently, the great desire to obtain relics led to the commercial exchange and even theft of them. Rome, with its numerous catacombs filled with the remains of the earliest Christians, was one of the key centres of the relic trade. It also became the most prominent Western pilgrimage site at a time when pilgrimage, at first to local shrines and then to international ones, became increasingly important. The desire on the part of the faithful to be buried near relics changed funeral practices. Ancient cemeteries were abandoned, and burials in or near churches (burials ad sanctos) increased.

The influence of the church on society and legislation

The progressive Christianization of society influenced Frankish institutions significantly. The introduction of royal consecration and the creation of the empire afforded the clergy an opportunity to elaborate a new conception of power based on religious principles. The church was involved in trying to discourage slavery and in ameliorating the legal condition of those enslaved. It was during the Carolingian period that, in reaction to the polygyny practiced in German society, Christian doctrines of marriage were more strictly formulated.

Merovingian literature and arts

During the entire 6th century many writers, inspired by Classical tradition, produced works patterned on antique models; such writers included Sidonius Apollinaris (died c. 488) and Venantius Fortunatus (died c. 600). In the late 6th century, Gregory of Tours produced influential works in history and hagiography—the writing of saints' lives, which became the most widespread literary genre of the period. Nevertheless, the standard of literature continued to decline, becoming more and more conventional and artificial. The use of popular Latin became more common among writers.

Religious architecture remained faithful to the early Christian model (churches of basilican type, baptisteries, and vaulted mausoleums with central plans). Because of the development of the cult of saints and the practice of burying ad sanctos, mausoleums became common in churches. As had been the case in antiquity, marble was the principal sculptural material. In the Pyrenees, sculptors produced antique-style capitals and sarcophagi, which they exported throughout Gaul; these workshops reached their zenith in the 7th century. The development of the art of metalwork (fibulae, buckles) was another characteristic of the Merovingian age. Germanic craftsmen adapted Roman techniques (e.g., cloisonné and damascene work). A new aesthetic standard, characterized by the play of colour and the use of stylized motifs, eventually predominated.

Carolingian literature and arts

Although its roots can be traced to the 7th century, a cultural revival, or renaissance, blossomed under the Carolingians. Indeed, the Carolingian kings actively promoted the revival as part of their overall reform of church and society. Inspired by his sense of duty as a Christian king and his desire to improve religious life, Charlemagne promoted learning and literacy in his legislation. He also encouraged bishops and abbots to establish schools to educate the young boys of the kingdom. His reforms attracted some of the greatest scholars of his day, including the Anglo-Saxon Alcuin and the Visigoth Theodulf of Orléans. The renaissance continued into the 9th century and gained renewed support from Charles the Bald, who sought to revive the glory of his grandfather's court.

After raising the standard of the clergy, Charlemagne assembled a group of scholars at his court. Although, contrary to legend, there was no formal school established in the imperial palace, numerous schools opened in the vicinity of churches and monasteries. An attempt was also made to reform handwriting. Research was carried on simultaneously under the auspices of several monastic centres (most notably Tours) for the purpose of standardizing writing; this effort resulted in the adoption of a regular, easily readable script (Carolingian minuscule). Improved teaching and a desire to imitate Classical antiquity helped to revivify the Latin used by writers and scribes.

The imperial court and monasteries throughout the realm were centres of literary production. Carolingian authors produced a number of works of history, such as Einhard's Vita Karoli Magni (Life of Charlemagne), the Astronomer's Vita Hludowici imperatoris (Life of Louis the Pious), Nithard's Historiarum libri IV (History of the Sons of Louis the Pious), and Hincmar's De ordine palatii ("On the Government of the Palace"). They also wrote original works of theology on such matters as predestination and the Eucharist. These authors also copied numerous works of Christian and Classical antiquity, which otherwise would have been lost, and Alcuin prepared a new edition of St. Jerome's Vulgate. Many of the more important books were beautifully illustrated with miniatures, sometimes decorated in gold, that revealed the Roman, Germanic, and Christian influences of these artists and their patrons.

Beginning in the mid-9th century, however, the kingdoms formed from the partitions of the empire saw a renaissance of regional cultures. The fact that the Oath of Strasbourg was drawn up in Romance and German is an early indication of this development. There is a striking contrast between the Annales Bertiniani (The Annals of St. Bertin), written at the court of Charles the Bald, and the Annales Fuldenses (The Annals of Fulda), written at the principal intellectual centre in Francia Orientalis. They are, respectively, the western and eastern narratives of the same events.

Some of the great imperial monuments erected during the Carolingian age (palace of Ingelheim, palace of Aachen) reveal the permanence of ancient tradition in their regular plans and conception. The churches were the subjects of numerous architectural experiments; while some were constructed on a central plan (Germigny-des-Prés, Aachen with its internal octagon shape), most remained faithful to the traditional T-shape basilican type. Liturgical considerations and the demands of the faith, however, made certain modifications necessary, such as crypts on the east or a westwork, or second apse on the west. These church buildings afforded architects an opportunity to make experiments in balancing the arches. The extension of the vaults over the entire church and the more rational integration of the annexes and church proper gave rise to Romanesque architecture.

The buildings of the period were richly decorated with paintings, frescoes, painted stucco, and mosaics in which figural representation increasingly replaced strictly ornamental decoration. North Italian ateliers were popularizing the use of interlace (i.e., ornaments of intricately intertwined bands) in chancel decoration. Sumptuary arts became more common, especially illumination, ivory work, and metalwork for liturgical use (reliquaries).

Gabriel Fournier

Bernard S. Bachrach

Jeremy David Popkin

The emergence of France